Institute of Middle East, Central Asian and Caucasus Studies Essay Competition: ‘Understanding Legacies of Imperialism in the Middle East, Central Asia and the Caucasus’.

The Chinese Dream: Dreaming as Constructing in the Definition and Self-Definition of China.

This essay was submitted by Florence Jones, of the Graduate School for Interdisciplinary Studies MLitt Global, Social and Political Thought programme, to the MECACS Essay Competition. Ms Jones’ research is focused on Nationalist Imagery and ideological Nation-building, which is a core theme for this engaging essay and has been awarded an Honourable Mention in the postgraduate category. Although the research is not focused directly on one of the MECAC regions, the panel deemed this essay to be worthy of an award due to its strong engagement with the competition themes and the importance of post-colonial studies in academia.

Introduction

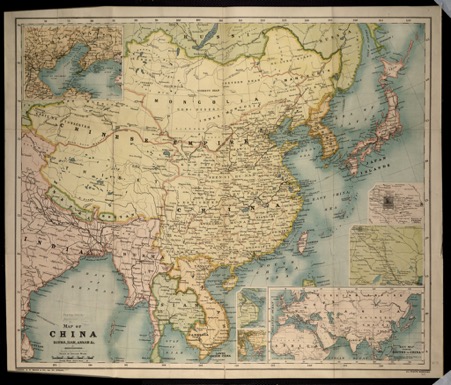

China, much like all other nations, is an object of construction (Anderson, 2016). The concept of ‘Asia’, and more specifically China, is the product of Western colonial-style invention, having no tangible meaning until it was forced upon other populations by external European forces (Lee, 2018). The name ‘China’ itself originates from Duarte Barbosa, a sixteenth-century Portuguese travel writer, bearing little resemblance to the Mandarin word Zhongguo 中国 which has only relatively recently developed as a means of denoting collective consciousness of the Chinese nation (Lee, 2018). As such, the geographical space that Western thought has assigned as ‘China’ has an extensive history of construction; the multitude of complex forms which this construction takes can be interpreted as kinds of dreaming. Our contemporary understanding of global politics is centred around ideas of North, South, East and West and notions of essential difference between each. The global stage has become defined by antagonisms between nations, built upon the foundations of post-World War II Area Studies, which seek to attribute specific socially constructed imaginaries to individual nations creating a global order wherein states are defined by, and limited to, an essential set of characteristics (Lee, 2008). Sinophobia, or an aversion towards China and that which the Chinese space represents, has come to define much of contemporary international collaboration, with such sentiments only appearing more frequently in discourse surrounding the climate contribution of various nations in the face of global temperature rise (Yu et al., 2019). As recently as 2021 in Glasgow for the 26th Conference of Parties (COP26), China was berated in the international media for failing to commit to lowering their coal consumption and associated emissions (Harvey, 2021a; 2021b; Yu et al. 2019) with little to no acknowledgement of the injustice associated with such a critique. Western media outlets were, for the most part, unwilling to accept that China is simply enacting an anthropocentric system inherited from the economically dominant ‘West’ (Castro, 2016; Chan et al., 2016; Lee, 2018; Peet, 2011). It can be argued that this lack of nuance is in fact a thinly veiled reproduction of many of the stereotypes Western societies hold when it comes to China. Chinese people and those of Chinese heritage continue to face prejudice and racist assumptions in Western societies, this bigotry is insidious, in many cases going unquestioned where prejudice towards those of other ethnic backgrounds would be deemed unacceptable (Lee, 2003; 1996). Given Western nations’ hostility towards China in a geopolitical sense, this prejudice could be suggestive of a wider disdain towards the Chinese and their diaspora.

Constructs of China and its inhabitants have deep historical legacies rooted in the era of European colonial-imperial expansion (Lee, 1996; 2003; 2018). Central to this construction are ideas of dreaming and dream-like narratives both through the orientalising and self-orientalising processes, as well as, in our contemporary era, as China asserts itself as a major player within the virulent neoliberal global hierarchy. In many ways China represents that which the West does not wish to see, the glaring results of our violent system of free-market capitalism and extreme industrialisation.

Forgetting as Dreaming

Recent calls in academia and scholarship suggest a desire for the decolonisation of the curriculum and an exposure of colonial realities to those studying at academic institutions in the West (Mheta et al., 2018). While these efforts are admirable, a collective amnesia seems to have taken root when it comes to the subjugation of China to colonial style forces (Rofel, 1999). Although China, in its entirety, was never formally colonised by European imperialists, to suggest that as a result China is completely uninfluenced by colonial-style forces is to neglect the fact that Western discourses which seek to dismiss ‘the East’ are fundamentally rooted in the colonial process despite the absence of the brute force of colonialism (Hayot, 1999). Colonialism is as much an ideological process as a physical, economic one with the ideals of Western societies being forcibly imposed on others and their world views being subsequently dismissed as at best quaintly infantile and at worst perverse and morally degenerate.

As an ancient society, China has been repeatedly portrayed as archaic and outdated with the Chinese language also being depicted as somehow underdeveloped or primitive (Lee, 2003). Even today, much Chinese thought is relegated to the realm of the ‘traditional’ bearing little resemblance to contemporary society. The East is fundamentally a construction by the West, the West has embedded itself in the idea of the East since its inception (Lee, 2008). In attempting to study the ‘East’ or China as an object is to necessarily also study the West and its construction of Asia. Erasing these realities create a dream-like conviction on the part of Western powers wherein they feel a sense of justifiability in the critique of the economic advancement of nations such as China in a discerningly similar spirit to the original logic of imperialist expansion. In relegating the Other, the West can justify its dream of ‘Western Liberal Values’ and its forceful imposition on other global societies (Appiah, 2018).

Orientalising as Dreaming

Pivotal to the West’s perception of China, and subsequently its surrounding area, are orientalist tropes (Lee, 2003). When considering notions of dreaming, visual representations of China and the cult of Chinoiserie are particularly relevant. ‘Chineseness’ has been repeatedly aestheticised, never more fervently than during the peak of Georgian fashion for the baroque with artists such as François Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard depicting a brightly coloured, rich, dream-like China bear little to no resemblance to lived reality during this era, often conflating confused impressions and incongruous elements of an imagined China which are the result of European construction rather than any genuine ethnographic interest (Auricchio, 2007; Said, 1979). This Chinese dreamscape where white Europeans can escape the rigid constraints placed upon them by their society preserves the influence of colonialist epistemologies which seek to maintain the dominance of Western hegemony on the world stage (Said, 1979 Witchard, 2015; Porter, 1999). Not only does this dominance take place through the physical process of colonisation but also through the creeping influence of ideological colonisation.

The long-held association between China and opium is also interlaced with notions of dreaming and escapism in the Western cultural imaginary of China. Following the growth of the trade, increasing the availability of the drug in Britain, the use of opioids, including laudanum, became common practice among middle class British society (Lee, 2003). While this was accepted and encouraged, the opium wars in China and subsequent typecasting of the Chinese as the addicted opium eater display a transparent double-standard. This parallel drawn between Chinese populations and drug-use frequently recurs especially in relation to areas with higher levels of Chinese immigration (Lee, 2003). These narratives present the Chinese as lacking resolve, hedonistic and morally questionable, wishing to escape their reality.

Orientalist tropes which seek to stereotype the Chinese take on various forms, affecting individuals differently. While Said’s original Orientalism was not intended as a work of feminist theory, it has subsequently inspired large amounts of scholarship as to the positioning of the orientalised woman (Abu-Lughod, 2001). Applying a gendered lens to our understanding of the perception of the ‘Chinese Other’ sheds light upon the ways in which these stereotypes take hold. Chinese women, and women of Asian heritage more generally, have extensively been associated with sexual promiscuity and ‘dirtiness’ (Lee, 1996; Nemoto, 2006). The fashion for Chinoiserie, through its many iterations, has been deeply feminised, as epitomised by essayist Charles Lamb’s shameful admission of his taste for feminine chinoiserie porcelain and other dainty ornaments (Witchard, 2015). Thus, not only does Chinese femininity become associated with that which is fragile and frivolous, but it is also both fetishised and demonised sexually (Hatzaw, 2021). Depictions of the Chinese woman, in a deeply orientalised fashion, can be understood through the lens of dreaming, both the ethereal, dreamlike, fragile quality but also the more illicit male fantasy, with Asian women as the site of clandestine male desire. One need only to look to the Madame Butterfly trope used across popular culture which portrays Asian women as overly feminine, exotic and sexual as well as being passive and yielding to this male desire (Nemoto, 2006).

For women of Asian heritage, the designation as the Other takes on a particularly violent quality, these women are the ultimate other, given their status as both ‘foreign’ and female, and inhabit a particularly precarious position in Western societies (Kim, 2016). De Beauvois conceptualises the female body as a physical site of male colonisation (1986), this has even greater pertinence when considering the intersectional identities of Asian women. Understanding Western dominance through this gendered lens can foster a better understanding of the way in which the other is both dominated and feminised to justify physical and ideological exploitation, as embodied by China.

Self-Orientalising as Dreaming

To simply view the Chinese as passive recipients of the pressures of orientalism fails to acknowledge the complexities of the interrelated nature of both Chinese and Western thought (Dirlik, 1996). Orientalism constructs itself upon a bedrock of everyday cultural practices which can no longer be distinctly divided into that which is Chinese and that which is Western (Dirlik, 1996). Confucianism and its legacies in Chinese intellectual history have a deeply intertwined relationship with the processes of orientalisation and self-orientalisation. Originally considered a deeply conservative ideology centred around ideas of the power of the state, patriarchy and the nuclear family, Confucianism has experienced somewhat of a reframing under the modern Neo-Confucians who seek to advocate for the use of Confucian pragmatism to facilitate capitalist modernisation in competition with the West (Bougon, 2018; Dirlik, 1995; 2016; Gu, 2001). Under this school, Confucianism is favoured as it represents a pure form of Chinese thought separate from the forces of orientalisation, and as such has been employed as a counterpoint to the intellectual hegemony of the West in promoting a modern China which is independent of the dominance of the West.

This ideology stands in stark contrast with the thinkers of the May Fourth movement who advocated for the modernisation of China through the promotion of Western Liberalism and Democratic ideology at the beginning of the 20th century and then reignited in line with the People’s Movement on Tiananmen Square in 1989 (Gu, 2001; Dirlik, 1995). However, as Dirlik outlines, Confucianism facilitates the preservation of central ideas of Chinese values and ideology in tandem with China’s ascension in global capitalist hierarchies (1995). By attaching such significance to the role of Confucianism within the nation-building project of China these Neo Confucian academics have themselves contributed to the very process which they are trying to avoid, the orientalisation of Confucianism, and self-orientalisation more generally (Dirklik, 1995; Lee, 2018). In trying to assert their difference from the ‘West’, China has often turned to orientalised tropes, which have their roots in Western perceptions of China (Dirlik, 1995; Lee, 2018; Lau, 2007; Dubrovskaya, 2019). This search for The Chinese Dream, an essential ‘Chineseness’, had taken on a particular pertinence in recent decades with the leadership of Xi Jinping.

Modernising as Dreaming

Given our ideological enslavement to the ideas of East and West within global relations and the continued legacies of cold war antagonisms China is continually presented as a threat to the values and worldview of the neoliberal, capitalist West (Knüsel, 2012). Under the leadership of Xi Jinping, China has occupied an increasingly competitive position within economic world markets, functioning as a hyper-capitalist global player whilst domestically operating under a strict system of official state communism (Bougon, 2018). Having been shoe-horned into a system which views progress under the strict definition exported via Western colonialism and economic domination, much of the rhetoric in contemporary Chinese politics associates Westernisation with modernisation (Bougon, 2018). Adopting from the American cultural imaginary, Jinping has successfully constructed notions of ‘The Chinese Dream’ drawing on much of the ideology associated with its counterpart ‘The American Dream’, despite the hugely different cultural contexts in which these narratives take root.

Notions of dreaming are thus central to the way in which China constructs itself in the face of Western hegemony. This dream is centred around economic advancement, with neoliberalism as the aspirational ideal, despite the fact that the vast majority of Chinese citizens continue to live under a state system which limits their choices and freedoms; as such this dream narrative primarily serves the self-aggrandisement of the state (Lee, 2018; Lin and Zhang, 2018; Kirby, 2004). As China becomes a direct competitor to the capitalist West, as the second largest economy in the world, Sinophobia and its associated prejudices continue to play a role in global relations with China. Much of our perception of China, and the ways in which we are encouraged to think about the state through both media portrayal and political discourse, can be interpreted as the dominant West negotiating the extent to which they are willing to allow the Chinese access to a system of Western dreaming which allows for economic advancement and neoliberal ‘success’. Western stereotypes of the Chinese diaspora as having escaped a miserable existence in order to pursue Western visions of success, such as through the child prodigy trope, remain a question of dreaming and desiring, with the Chinese hoping to achieve this dreamscape of a Westernised definition of success.

Conclusion

Employing the language of dreaming and dream-like narratives when considering the ways in which China has been defined and redefined throughout its enmeshed history with the West illuminates the extent to which these narratives are the objects of construction. In our contemporary era of extreme globalisation, collaboration and coexistence between nation states is vital if we are to find solutions to contemporary societal questions be them environmental degradation, cross-border collaboration or the establishment of a more just society. Our global order is still fundamentally entrenched in systems of Western dominance with those representing anything other than Westernised definitions of success being dismissed, be that through official political discourse and debate or on an individual level in what is still a fundamentally racist society (Lee, 1996). Given political relations between Western nations and China, Sinophobia has become normalised with unjust critique and dismissal being levelled at the state and the individual on a regular basis. While we may question certain practices of the Chinese government we must transcend our prejudices and recognise China’s role in enacting what is, at its core, a Western definition of modernity (Lee, 2018). China has been ideologically positioned as the ultimate Other to Western rationality (Longxi, 1988); Acknowledging the construction narratives associated with China and Chinese people and the extent to which the West has, historically and continually today, implemented itself in the definition of China could be a meaningful first step in the deconstruction of this othering and a path to a more constructive relationship.

Bibliography

Abu-Lughod, L. (2001). Orientalism and Middle East Feminist Studies. Feminist Studies. Vol. 27(1). Pp. 101-113.

Ambrogio, S. (2020). On the First Step of “Chinese Irrationality”: Early Christian Definition of Buddhism as a Useless Doctrine in Late Ming China. International Communication of Chinese Culture. 7. Pp 467-484.

Anderson, B. (2016). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Verso: London.

Appiah, K.A., (2018). The Lies That Bind: Rethinking identity. Profile Books: London.

Auricchio, L. (2007). Reviewed Work(s): Making up the Rococo: François Boucher and his Critics by Melissa Hyde: Rethinking Boucher by Melissa Hyde and Mark Ledbury. The Art Bulletin. Vol. 89(3). Pp. 597-601.

Bougon, F. (2018). Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping. Hurst and Company: London.

Castro, P. (2016). Common But Differentiated Responsibilities Beyond the Nation State: How Is Differential Treatment Addressed in Transnational Climate Governance Initiatives? Transnational Environmental Law. 5(2). Pp 379-400.

Chan, S., Brandi, C., and Bauer, S. (2016). Aligning Transnational Climate Action with International Climate Governance: The Road from Paris. Review of European Community and International Environmental Law. 25(2). Pp238-247.

De Beauvoir, S. (1986). La Deuxième Sexe. Gallimard: Paris.

Dirlik, A. (1995). Confucius in the Borderlands: Global Capitalism and the Reinvention of

Confucianism. Boundary 2. 22 (3). Pp 229-273.

Dirlik, A. (1996). Chinese History and the Question of Orientalism. History and Theory. Vol.

35(4). Pp. 96-118.

Dirlik, A. (2016). Modernity and Revolution in Eastern Asia: Chinese Socialism in Regional Perspective (東亞的現代性和革命: 區域觀點下的中國社會主義). Translocal Chinese: East Asian Perspectives. 10 (1). Pp 13-32.

Dubrovskaya, D. V. (2019). Orientalism and Occidentalism: When the Twain Meet. Vostok. Afro-asiatskie Obshchestva: Istoriia I Sovremennost. Vol. 5. pp . 77-82.

Gu, E. X. (2001). Who Was Mr Democracy? The May Fourth Discourse fo Populist Democracy and the Radicalization of Chinese Intellectuals (1915-1922). Modern Asian Studies. Vol. 35(3). Pp. 589-621.

Harvey, F. (2021a). Joe Biden Lambasts China for Xi’s Absence from Climate Summit. The Guardian. [online]. 2 November 2021. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/nov/02/cop26-joe-biden-lambasts-china-absence. Accessed on: 21/11/21.

Harvey, F. (2021b). China’s Top COP26 Delegate Says it is Taking ‘Real Action’ on Climate Targets. The Guardian. [online]. 10 November 2021. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/nov/10/chinas-top-cop26-delegate-says-it-is-taking-real-action-on-climate-targets. Accessed on: 21/11/21.

Hatzaw, C. S. S. (2021). Reading Esther as a Postcolonial Feminist Icon for Asian Women in Diaspora. Open Theology Vol. 7(1). Pp.1-34.

Hayot, E. (1999). Critical Dreams: Orientalism, Modernism, and the Meaning of Pound’s China. Twentieth Century Literature. Vol. 45(4). pp . 511-533.

Kim, G. S. (2016). Hybridity, Postcolonialism and Asian American Women. Feminist Theology. 24(3). Pp. 260-274.

Kirby, W. C. (2004). Realms of freedom in modern China (Vol. 15). Stanford University Press: Stanford.

Knüsel, A. (2012). Framing China: Media Images and Political Debates in Britain, the USA and Switzerland 1900-1950. Routledge: Abingdon.

Lau, L. (2007). Re-Orientalism: The Perpetration and Development of Orientalism by Orientals. Modern Asian Studies. Vol. 43(2). Pp. 571-590.

Lee, G. B. (1996). ‘Fear of Drowning: Pure Nations, Hybrid Bodies, Excluded Cultures’. In

Troubadors, Trumpeters, and Troubled Makers; Lyricism, Nationalism and Hybridity in China and its Others. Duke University Press: South Carolina.

Lee, G. B. (2003). China’s Unlimited: Making the Imaginaries of China and Chineseness. University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu.

Lee, G. B. (2008). Taking Asia for an Object- The Big Mis-Take. [Workshop]. EastAsiaNet.eu Workshop. 30-31/05/2008. Available at: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00322535/file/_Leeds_EAN_31_May_2008_LEE.pdf [Accessed: 10/03/2022].

Lee, G. (2018). China Imagined from European Fantasy to Spectacular Power. Hurst & Co.: London.

Lin, F., and Zhang, X. (2018). Movement- Press Dynamics and News Diffusion: A Typology of Activism in Digital China . China Review. 18(2). Pp. 33-64.

Longxi, Z. (1988). The Myth of the Other: China in the Eyes of the West. Critical Enquiry. Vol. 15(1). Pp. 108-131.

Mheta, G., Lungu, B.N. and Govender, T. (2018). Decolonisation of the Curriculum: A Case Study of the Durban University of Technology in South Africa. South African Journal of Education. Vol. 38(4). Pp. 1-7.

Nemoto, K. (2006). Intimacy, Desire, and the Construction of Self in Relationships Between Asian American Women and White American Men. Journal of Asian American Studies. Vol. 9(1). Pp. 27-54.

Peet, R. Robbins, P. and Watts, M. (2011). Global Political Ecology. Routledge: Abingdon. Porter, D. (1999). Chinoiserie and the Aesthetics of Illegitimacy. Studies in Eighteenth-Century

Culture. Vol. 28. Pp. 27-54.

Rofel, L. (1999). Other Modernities: Gendered Yearnings in China After Socialism. University of

California Press: Berkeley.

Said, E. W. (1979). Orientalism. Vintage Books (Random House New York): New York.

Witchard, A. (2015). British Modernism and Chinoiserie. Edinburgh Scholarship Online. [ebook]. Available at: https://edinburgh-universitypressscholarship-com.ezproxy.st-andrews.ac.uk/view/10.3366/edinb urgh/9780748690954.001.0001/upso-9780748690954-chapter-001 [Accessed: 7/3/22].

Yu, B., Zhao, G. & An, R. (2019) Framing the picture of energy consumption in China. Natural Hazards. 99. Pp 1469–1490.