Mapping Kurdistan: Territory, Self-Determination and Nationalism – A seminar with Dr Zeynep Kaya

This report was authored for the Institute by Oliver Mizzi, MECACSS MLitt Student.

On the 17th March 2022, Dr Zeynep Kaya presented a talk centred on her newly published book, Mapping Kurdistan: Territory, Self-Determination and Nationalism.

To open the discussion, Dr Kaya first mentioned the map of the imagine Kurdish homeland, a land that spreads across four Middle Eastern states; Iran, Iraq, Turkey and Syria. Not only does this introduce the popular conceptions of a Kurdish homeland, it also highlights the complexities and peculiarities of the Kurdish struggle for territory, self-determination, and conceptions of nationalism.

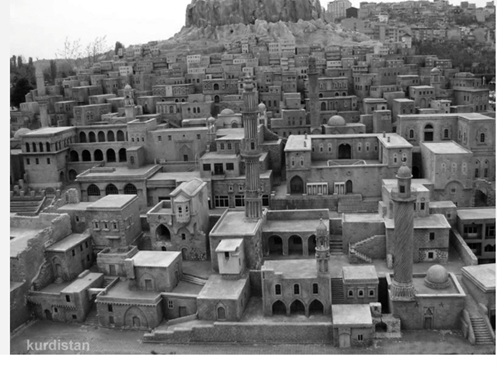

“Kurdistan stone houses” by Kurdistan Photo كوردستان is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

It is from this starting point that Dr Kaya discussed her research, doing so by navigating the history of Kurdish struggles for self-determination throughout the late 19th and 20th century. This navigation is particularly interesting because, whilst linear in narrative, it is structured by highlighting three distinct periods of transformation in the international environment that defined how Kurdish self-determination was conducted.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the final decades of the Ottoman Empire, Kurdish tribal elites and intelligentsia were exposed to new ideas surrounding nationalism and self-determination whilst attaining education in cities in Europe, as well as in Istanbul, with some beginning to publish journals starting from the 1880s. In addition to the formation of nationalist sentiment, elites also started aligning with the different forces that were forming in the empire, which would be important following the first transformation in the international environment.

The first big transformation is the First World War which saw the breakdown of the Ottoman Empire and the rise of the modern Turkish Republic. In this space different Kurdish organisations emerged seeking their own distinct statehood, but with Turkish success during the Turkish war of independence, Kurdish statehood failed to materialise. This was in-part due to the abandonment of the idea surrounding Kurdish statehood by its would be international patrons – the victors of WW1. It is also in this environment of newly won statehood for former Ottoman provinces that Kurds found themselves inhabiting distinct national contexts which would define the character of Kurdish organizations.

The second big transformation came in the form of de-colonization and the rise of self-determination across much of the world in the post-Second World War period. In line with this international sentiment, so too did Kurdish nationalism rise as part of a wider moment of national self-determination, including Kurdish organisations dedicated to armed struggle for self-determination like the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) in Iraq and the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) in Turkey. Moreover, cross border connections develop between Kurdish organisations, and waves of Kurdish migration to Europe solidified a politically active diaspora, writing about Kurdish struggles in the Middle East.

“Kurdistan Flag” by Jeffrey Beall is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

This of course leads to the third big transformation: the end of the cold war and the rise of the human rights framework in the international system. This has major affects for Kurds in the Middle East and in Europe, with an increase in activism on the basis of human rights, and the creation of a Kurdish autonomous zone after the 1991 gulf war which becomes solidified after 2003.

In light of the development of the Syrian Civil War, Dr Kaya also talks about the contrast between Kurdish groups as well. For instance the split between the KDP and the PKK because of divergences between ideologies and nationalism, whereby the KDP aspire for traditional nation-statehood, and the PKK transcending the aspiration for a Kurdish nation-state and aspiring for Democratic Confederalism instead.

Throughout the talk, Dr Kaya looks at Kurdish struggle from a non-state perspective, and with Kurds as international actors themselves. This is because Kurds have interacted with the international system in a variety of ways outside of the state apparatus. This includes as a diaspora attempting to spread awareness of Kurdish rights in the Middle East in Europe. Likewise, as armed non-state actors that are fighting for statehood, and forming ties between Kurdish organisations across borders, internationalising their issue for the regional system.

“Nexshei-kurdistan Map” by Kurdistan Photo كوردستان is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Dr Kaya’s research highlights a relational perspective to the international – whereby non-state actors still inhabit the international space, interacting with states both in the region and outside of it, such as in Europe or the United States. Moreover, she points to historical sociology as being able to help scholars understand the changes in the international environment, and how Kurds as international actors have a relationship with the transformations in the international environment.

A question and answer session followed from the initial talk where audience members asked a variety of questions relating to the themes that were brought up during the talk. Many of these questions surrounded intra-Kurdish divisions and the inability of Kurds to unite to form a single state.

In response to these Dr Kaya discusses a few points. For instance, Kurds exist in a unique position in the Middle East, being a mountainous region at the crossroads of empire and the peripheries of states meaning central authority has never been able to properly penetrate into the region. Thus, tribal authority has negotiated authority, and carved out their own authority.

This is important because the region has also had a difficult history given the huge political developments of the fall and rise of governments and states throughout the 20th century. This has meant that Kurds have had to respond to different political, economic and military events around them for the purposes of survival, and the same occurs in the present day as can be seen with the rivalry between the PUK and KDP in Iraqi Kurdistan. This has in turn led to opportunities to form a singular state being marred with various divisions such as between different patronage systems that seek to retain authority.

“KURDISTAN” by Kurdistan Photo كوردستان is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Moreover, when compared to successful political movements after World War 1, it is clear that singular political leadership and strong mobilization of human capital and the economy was important for establishing a nation-state, which was lacking in the Kurdish case as noted above, in particular because the mountainous region is so large.

Thus it’s important to understand Kurds and their context in a deeper way, moving away from a European idea of nationhood that focuses on Kurds inability to form such a nation-state simply because of political disunity. Rather we should understand why, and this takes the form of looking at history, sociology and geography.

Likewise, other questions surrounded the current state of Kurdish liberation struggles in the context of division, thus prompting conversations on the PKK and Rojava in Syria.

For instance, when discussing a the inability of Kurds to move past intra-political rivalries and lacking cross border solidarity, Dr Kaya notes the PKK as an example of an organisation that has sought to cross national boundaries and garner support from the different countries that Kurds live in, as well as diaspora communities in Europe. Moreover, the organisation utilizes it’s leftist ideology to discuss questions surrounding topics such as freedom. Whilst, it does share this with other Kurdish parities, it is more disciplined, which perhaps means it’s able to cross national boundaries better.

Likewise, in answering a question on how revolutionary Rojava is, Dr Kaya notes that whilst some activities are revolutionary, other activities are counter-revolutionary, most notably in their policy towards rival political parties. Thus the question must be asked, if Rojava achieves its goals of independence from the Syrian regime, will it become a democratic confederalist or an authoritarian entity.

Regarding the impact of the Syrian Civil War for Kurdish issues, it is very different from the impact of the Gulf War. Whilst it didn’t lead to an internationally recognized state, it did give more legitimacy to the PKK because of it’s connections to the PYD in Syria and their alliance with the US in fighting ISIS. This of course is a big change in the PKK’s history and their position in the Middle East.