Report – Cultural and religious identity during the Syrian uprising

On 11th March 2022, the Institute of Middle East, Central Asia and Caucasus Studies and the Centre for Syrian Studies co-hosted a workshop on Cultural and Religious Identity during the Syrian Uprising as part of the University of St Andrews Sanctuary week. MECACS Director Dr Fiona McCallum Guiney and the Head of the School of Classics Rebecca Sweetman served as academic mentors to Syrian colleagues as part of the Council for At-Risk Academics (CARA) Syria programme.

This enlightening workshop provided a clear understanding of the present situation of Syrian minority groups and the cultural heritage of Syria in the period following the Syrian uprising of 2011 and subsequent conflicts. Dr. Nidal Ajaj and Dr. Samir Alabdullah presented a case study on current tensions arising between religious populations within Syria, exploring the impact of the conflicts on the Christian community and its various political positions as a result of sectarian tensions under the Assad regime. Dr. Mahmoud Zin Alabidin then presented a range of examples of cultural heritage buildings from Aleppo which have experienced cycles of damage and reconstruction to varying extents, emphasising the importance of architecture to the social fabric and identity of the community in Aleppo. The presentations were complimentary and provided a thought-provoking springboard for the enlightening discussion which followed – with discussants Prof. Rebecca Sweetman and Dr. Andreas Schmoller. Asma’ Shihadeh contributed as an excellent translator, who helped the discussion flourish as it overcame lingual barriers.

Dr. Nidal Alajaj opened the first talk, The Situation of Syrian Minorities after 2011: Christians as an example, by outlining the multifaceted nature of the situation of minorities in the Middle East. He accurately identified this highly complex issue, only complicated further in the mid-nineteenth century when external countries began interfering with the region’s affairs on the pretext of ‘protecting minority rights.’ For Syria, this is apparent from the diminishing presence of Christians in the region, which has had multiple waves of Christian emigration since the second half of the nineteenth century. Alajaj explained that the population of Christians (from various denominations) dropped from 25% of Syria’s population after the Second World War to just 8% shortly before the 2011 revolution, and this has since declined further to 3.5% in 2021. Since Bashar al-Assad’s transition to power in 2000, his regime has played a large role in instigating conflicts in the region by claiming to adopt a secular approach whilst simultaneously exploiting religious institutions and inter-ethnic tensions for a tighter grip on the community. Christian leaders have been granted privileges in exchange for complete loyalty, and groups are divided as leaders from minority groups have allied with the Assad regime, justified by their fears of sectarian threats.

Research questions presented by Alajaj and Alabdullah included how the situation of Syrian Christians has changed since 2011, what the nature of relations between the Syrian Christian community and different dominant forces in Syria, and what roles have Christians played in different areas in Syria since 2011. The project had several key findings. The researchers identified the role that the Assad regime played in religious tensions, finding that it relied on manipulating religious discourse within the community and responsible for using excessive violence against the opposition during the 2011 protests in order to push them into an armed conflict, which the regime’s well-armed military forces were geared to win. Christian relations with the Syrian opposition were also strained, exacerbated by the kidnapping and murders of Christian leaders such as Bishop Yohanna Ibrahim and Bishop Boulos Yazigi in 2013. The situation of Christians in areas controlled by radical groups continues to be fraught, as the presence of radical Islamist factions within revolutionary spheres has fuelled fear amongst minorities. Likewise, areas recovered from ISIS occupation, and now controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), have considerable tensions, particularly as the SDF restricted curricula taught at schools and attempted to prevent the use of the Arabic and Syriac languages. Ajaj and Alabdullah warn us against assuming homogeneity amongst the Christian population in Syria, there are diverse groups and fighting is directed towards protecting areas of influence, there are also ethnic rather than religious divisions. A further key issue is the targeting of Christian places of worship, which has been done primarily by government forces and other related fractions. 63 Churches have been damaged by shelling, the Assad regime was responsible for 40 of these, the rest have been damaged by ISIS, Al-Nusra front, or otherwise unidentified groups. A further 11 churches have been used as military or administrative bases. This removal of key religious and cultural hubs has placed considerable pressure on the Christian community which has been displaced from its cultural, religious, and historic centre.

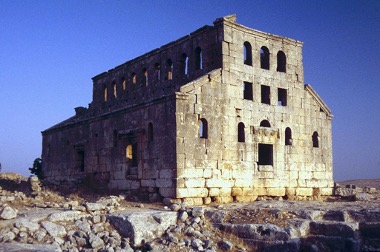

Dr. Mahmoud Zin Alabadin then presented on Syrian cultural heritage during conflict: From destruction to reconstruction and its impact on Syrian cultural identity – a case study from Aleppo. Alabadin’s informative talk discussed how the destruction of cultural heritage has affected the cultural identity of the city of Aleppo. He began by highlighting the continuity of the ancient city and its rich cultural fabric which is rooted in the ancient architecture. The presentation covered the most pressing obstacles facing restoration projects in Aleppo and evaluated some case studies of restoration projects to understand their purpose, how they comply with international standards, and the impact of the restorations on Syrian identity.

Key research questions for Alabadin’s project looked at the value of reconstructing damaged cultural heritage, and what this meant for the Syrian government and the lived experience of local communities on the ground. The project further assessed the criteria used by Syrian authorities to determine which buildings were to be reconstructed, evaluated whether the restorations met international standards and identified key obstacles to the success of these restoration projects. Alabadin summarised the destruction caused to the infrastructure and “urban fabric of the Old City of Aleppo” between 2012 and 2016. Alabadin presented research on five heritage sites in Aleppo: Umayyad Mosque – in the centre of the city, Al-Saqatiyah old Souk, Basil House, Beruia Restaurant, and Abu al-Huda al-Sayyadi House. Each case study included a historical introduction, an architectural description, an assessment of the damage caused by the conflicts, a description of the restoration work taking place, and an evaluation of restoration work. These sites are of intrinsic importance to the history and cultural fabric of the city – Umayyad Mosque is one of the earliest mosques built during the Umayyad period and is the largest mosque in Aleppo city. Al-Saqatiyah old Souk is in the heart of Aleppo and 38-40% of the covered souk has been destroyed.

Alabadin clarifies that the damage in Aleppo is not evenly distributed; the level of destruction differs from one area to another within buildings, as well as from one building to another. This makes the level of restoration required for each site unique, with some reconstructions more comprehensive than others, for example, the Madrasa of al-Khusruwiya was almost completely destroyed. Basil House was built in the 16th century, and extensive research was funded for the restoration which followed international standards and focused on the facades overlooking the interior courtyard. Beruia Restaurant was built in 1889 and was the first agricultural bank built during the Ottoman period, unlike Basil House, the restoration included modifications of the façade and reinforced concrete beams being added which distorted the original building’s identity. Abu al-Huda al-Sayyadi House was established in 1877 by Sheikh Mohammad Abu al-Huda, and despite suffering extensive damage during the war, the restoration was extensive and supervised by the Antiquities and Museums Directorate and in accordance with international standards.

The conclusions drawn by Alabadin were both illuminating and thought-provoking. It is clear from the project that a clear criterion is not used for selecting which heritage projects to undertake for restoration. Further obstacles are also presented when there is damage to private property. Financial considerations present some of the most challenging barriers to restoration. Alabadin found that priority was often given to projects that could obtain external funding; this meant that religious buildings and commercial property were prioritised, whereas the development of residential buildings and shops stagnated. Citizens were often left unable to cover the costs of restoration. The conflict has not just impacted the infrastructure of the city – the cultural and historic heart of Aleppo has suffered extensively.

Alajaj, Alabdullah and Alabadin concluded by emphasising the human cost of the conflicts. Alajaj stressed that the protracted crises caused the “displacement and emigration of millions of Syrians [and] is still ongoing.” The conflict continues to impact all Syrians and there has been little progress towards a peaceful resolution. Alabadin further emphasised that this displacement of people from Aleppo and Syria has resulted in an exodus of engineers, experts, and skilled workers, who would be able to properly restore the local infrastructure. A fluid discussion followed, raising important questions about the different pressures faced by communities in Syria, including the level of agency that minorities had in supporting the Assad regime, and the extent to which modern reconstructions of historic sites is impacting the identity of the city. The people of Syria have been dislocated from their land, and the rebuilding of key cultural heritage sites such as Aleppo must be prioritised to bring people home and to keep local identities alive. There is power in ‘bearing witness,’ in recognising the rich tapestry of identities in the region, and in maintaining an awareness of the impact that conservation efforts of historical heritage can have on communities who live in these disrupted spaces.

Sally Mubarak is a PhD candidate in the School of Classics, St Andrews. Her work examines war and trauma in the ancient Mediterranean. Her interests also include the role of socio-political boundaries, liminality, and identity in ancient military interactions as well as the impact of colonial research frameworks in the study of history.