Syria’s Long War – UCD and the Battle Between Ba’athist and Islamist

By Oliver Mizzi, postgraduate student in the Institute for Middle East, Central Asia and Caucasus Studies’ Security Studies programme. Oliver has developed a strong research interest in the Middle East, which is demonstrated in this engaging and informative essay. This essay was awarded the best postgraduate essay in the recent MECACS Institute essay competition.

Introduction

The Syrian Civil War is now in its 11th year. What started as a revolution against Bashar al-Assad’s dictatorship turned into a conflict pitting the Syrian government and its allies against a plethora of rebel organisations of various political identities from secular nationalist, Islamist, and Kurdish orientations (Yassin-Kassab & Al-Shami, 2016). However, this is not the first time Syria has suffered internal conflict between competing political groups. The harshest being the Islamist insurgency of 1979-1982 (Conduit, 2016). Yet both this conflict, and the contemporary conflict, are part of a wider long war in Syria; a war that has pitted two ideological orientations that arose under the same circumstances, but with wildly different visions of the future.

This essay will attempt to understand the long conflict between Ba’athists and Islamists in Syria utilising the approach of Uneven and Combined Development (UCD) to do so. By using UCD, and International Relations conceptualised as Societal Multiplicity, this essay intends on contextualising the development of both ideologies, situating them at a point when Syrian intellectuals were producing new ideologies to counter European hegemony, and provide a bright vision for the future of the region. Thus, as an outgrowth of societal multiplicity, two competing ideologies emerged and have become hegemonic in Syria’s political history, and who’s residue impacts Syria’s contemporary politics.

In doing so, this essay will first, outline what societal multiplicity is, as well as UCD. Secondly; apply UCD to the cases of Arab Nationalism and Islamism to demonstrate that they are products of societal multiplicity and of imperial legacies. Lastly; put forward a history of the long war between the Ba’athists and Muslim Brothers, showing how that legacy is reflected today.

Societal Multiplicity and Uneven and Combined Development

Uneven and Combined Development (UCD) is a theory of societal development that emerged out of Leon Trotsky’s attempt to understand the preconditions, and peculiarities of the Russian Revolutions of 1917 (Trotsky, 2017). UCD is predicated on three basic assumptions of the international (Rosenberg, 2016). The first is that the world is uneven in that it comprises of many different societies at different developmental stages. Second, their existence is combined in that they co-exist and interact with each other. Both these assumptions, which can be said to comprise societal multiplicity, result in the driving of historical development.

There are some other facets of UCD that are essential to the theory; Trotsky’s notion of the privilege of historic backwardness, and the whip of external necessity (Trotsky, 2017, p.4-5). Because of the combination of both the unevenness and combined nature of societal interactions, a whip of external necessity is produced whereby ruling elites need to develop their societies because of the unevenness of inter-societal co-existence (Rosenberg, 2016b). Yet, in the case of societies that are at an earlier stage of development – elites import developmental achievements into them: creating the privilege of historic backwardness whereby societies leap forward over intermediate developmental steps. What results is a unique developmental pattern exhibited in societies across the world, and as such – like in the case of Russia’s Bolshevik revolution (Trotsky, 2017) – there are a multitude of political outcomes, many of which at first seem peculiar.

It is this theory of societal development that will be utilised to understand the development of two rival ideologies of Ba’athism and Islamism in Syria. Whilst the whip of external necessity will be utilised to understand the necessity of intellectual elites to develop new indigenous forms of ideology, in line with the West and to act as a bulk ward against its encroachment – the privilege of historic backwardness ensures we understand that, although importing certain ideas from Europe, the new ideologies are still rooted in the local peculiarities. Moreover, because UCD is predicated on the principle of societal multiplicity, the analysis will always be grounded in the international context in which this ideological formation took place, giving us a sense of how the long war has imperial legacies in its foundations. For where Marx said that the “tradition of all past generations weighs like an alp upon the brain of the living” (Marx, 2006, p.8), so too does the outgrowth of the imperial moment weigh upon Syria today.

The next section will analyse the formation of these ideologies in light of UCD, starting in the late 19th century as the Arab Renaissance – the Nahdah – was emerging. Moving on from then, a reinterpretation of the formation of Arab nationalist and Islamist ideology will be conducted. The purpose is to contextualise how the imperial international system shaped both the necessity to develop new ideologies, as well as how the whip of external necessity ensures the rise of two competing visions of the future.

Ba’athism and Islamism: An outgrowth of Europe’s imperial moment

During the 19th century, the Middle East, like much of the world, had been experiencing increasing pressure of Western encroachment (Rogan, 2017). This encroachment stimulated administrative reformism in the Ottoman Empire, Egypt and Tunisia, with the purpose of emulating Western societies in order to resist them. Not only did the state apparatus undergo transformation, so too did secular and religious intellectuals.

The earliest example of this current is the 19th century Nahdah. This is one of the earliest cases of UCD at play, as Patel (2013) argues, Arab intellectuals saw the ‘need of the infusion of Western knowledge and learning for its cultural, social and political regeneration’ (p.177). This was taken up by both intellectuals that sought to revive the Arabic language and literature, as well as religious intellectuals that sought to revive Islam. By importing Western methods and practices and infusing them with a local peculiarities and intellectual traditions, the region could defend against Western domination over the region. Whilst the administrative reforms of the region failed to stop direct colonial administration, the intellectual purpose of the Nahdah – overcoming the ‘backwardness’ of the region – would have a lasting impact on new political currents that arose in the 20th century.

One such political current was Arab nationalism. A rising phenomenon throughout the region, Arab nationalist movements would revolt against the Ottomans, French, and British through the 1910s and 1920s (Barr, 2011). The most prominent intellectual that contributed the Arab nationalist current was Sati al-Husri who developed his own theory of the nation that widely influenced subsequent nationalist intellectuals. He combined the German idea of the nation, which constructed it in terms of common culture and language, and intertwining that with Ibn Khaldun’s social and historical philosophy, in particular the idea of asabiyya or as Husri would interpret it, a social bond between people with a common destiny (Tibi, 1997). His role as an educator in the Syrian and Iraqi education system, as well as the publications of his work across the region, influenced subsequent nationalist intellectuals (Dawisha, 2016).

These includes the Ba’athist theorists, most notably its main ideologue Michel Aflaq. Founded in 1947 by Michel Aflaq and Salah al-Din al-Bitar, the Ba’ath party proposed a secular, pan-Arabist and socialist modernization agenda that would take Syria out of its backwardness (Hinnebusch, 1990). Aflaq, along with Bitar, studied in Paris (Devlin, 1976), and during his time there came across a wide range of European philosophy as well as the political activity of Marxist leaning parties (Stegagno, 2017). This shaped the formation of the Ba’ath party, which resulted in a synthesis between ideas of Arab nationhood, anti-colonialism, and socialism. However, the fusion of the three is unique in that, socialism is actively subordinate to the Arab nationalism of the ideology, with the importance of class struggle being removed and replaced by the importance of Arab unity in light of European imperialism. Thus, socialism is the organizational basis for Arab liberation.

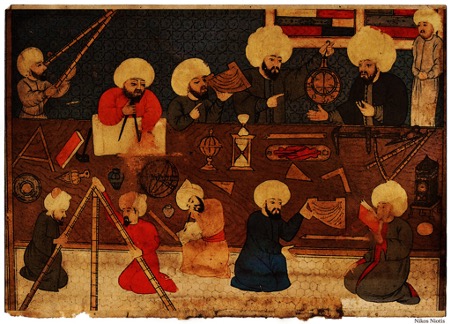

Whilst an Arab nationalist intellectual current that had formulated after the Nahdah, so too did a second intellectual current emerge; Islamism. The Islamist current had started forming as part of a wave of Islamic modernists in the late 19th century, with members of the Syrian Ulama such as Abd al-Qadir al-Jaza’iri (1807-1883) and his predecessors taking the lead (Commins, 1990). Jaza’iri, like his Egyptian counterparts, wanted to use reason to bring Islam and Islamic society into modernity and defend against Western supremacy. His education in scientific methods like mathematics and geography, and experience fighting French colonial forces in Algeria left an impression on him and his supporters, on the necessity of reform. Along with other Salafi intellectuals such as Abd al-Hakim al-Afghani, the lasting effect on Salafi intellectuals was the necessity of using Ijtihad, independent reasoning in Islam, to ensure that along with administrative reforms the Ulama could play a vital role in revitalising society. This importantly meant entering the public realm and civil politics, in particular, during the political and constitutional changes in the later years of the Ottoman empire.

Thus, by the time of the French mandate, Islam had already begun to enter the public realm, and would continue apace due to the furthering of education to the masses, and the reforming of both public and private, and Islamic and secular educational institutions in the image of Western educational systems (Pierret, 2013). Moreover, the existence of Jam’iyyat, or societies, from the late 19th century provided a constellation of organisations with the aim of reviving Islam in society. These organisations formed the backbone of a new organisation that would spearhead Islam in political life, the Muslim Brotherhood (Teitelbaum, 2011). The brotherhood was inspired by its Egyptian counterpart with the diffusion of the party from Egypt to Syria being facilitated by the fact that its leading figures Mustafa al-Siba’i and Muhammad al-Hamid became acquainted with its leader, Hassan al-Banna, during studies in al-Azhar University.

The Brotherhood sought an Islamic form of modernization to bring the region out of its ‘backwardness’. Whilst the Syrian brotherhood took on the infusion of Islam and secular politics by the Egyptian wing, helpfully summed up by the phrase ‘“The Koran is our constitution”’ (Kepel, 2002, p.27), the Syrian wing had some local distinctions. For instance the use of socialism by the brotherhoods early leader Mustafa al-Siba’i. In order to challenge the socialism of Ba’athism and the communist party, Siba’i phrased the brotherhoods terminology through the ‘“Socialism of Islam”’ (Teitelbaum, 2011, p. 224).

The Long War

Once Syria attained independence from France in 1946, the Ba’ath and the Muslim Brotherhood emerged as two political organisations that sought to push forward Syrian society into a better future. However these diverging visions of the future ensured a political rivalry in the post-independence political scene.

During this period the Brotherhood and Ba’ath fought electorally, vying for various segments of society such as the middle and working classes. Between 1947-63, the Muslim Brotherhood was actively involved in domestic politics, participating in electoral politics, with members wining seats in the Syrian parliament in 1947, 1949, and 1961 (Conduit, 2019a). In addition to participating in parliament, the Brotherhood also held weight in the various constitutional debates during the period, and its members held government ministries at various points.

Like the Brotherhood the Ba’ath had electoral experience, and executive experience. Their outreach was wide, incorporating many nationalist segments of society, including members of the Syrian military. The Ba’ath helped Syria unite with Egypt to form the UAR in 1958, and Ba’athist officers in the Syrian military launched a coup in 1963, disbanding Syria’s parliamentary democracy and enacting a Ba’athist modernization of Syria (Olson, 1982). Although the Brotherhood was banned in 1952, and 1958, it was only after the end of Syria’s parliamentary democracy resulting from the Ba’athist coup in 1963 that led to the Brotherhoods permanent ban.

In post-63 Syria, the contrasting visions of the future and the imposition of a secular Arab nationalist agenda by the new Ba’athist regime led to clashes between the regime and the Muslim Brotherhood. The Brotherhood, who were now outlawed, faced severe repression from the regime, with one of its leaders, Isam al-Attar, becoming exiled to Germany after the coup of 1963 (Abd-Allah, 1983). Both the Ba’athist regime and the Muslim brothers experienced a power struggle during the 1960s, with Hafez al-Assad coming out on top in the Ba’ath in 1970 (Van Dam, 1996), and the Muslim Brothers becoming split between a moderate and hard-line factions (Abd-Allah, 1983). One such hardline figure, Marwan Hadid, became an inspirational figure for those who wanted to wage Jihad against the state. Hadid had befriended Sayyid Qutb during his time in Egypt, and like Qutb, advocation for such action. Although Hadid was killed by the regime in 1976, the increased radicalization of the Brotherhood culminated in the formation of the Islamic Front in Syria in 1980, and a bloody conflict during the late 70s and early 80s. Whilst anti-regime sentiment was wide, typified by the assassination of Salah al-Din al-Bitar by the regime in Paris, the Muslim Brothers were the vanguard of this insurrection (Hinnebusch, 2001). This ultimately culminated in the 1982 Hama Uprising and the near destruction of the Brotherhood in Syria (Conduit, 2016).

Although dormant, the conflict between the two would again arise during the 2011 revolution and subsequent civil war. Although many of the Islamist organizations hold beliefs similar to those of the Muslim Brotherhood, the Muslim Brotherhood was not represented by a subordinate armed wing, only being able to support favoured groups externally, as well as having some shared membership (Conduit, 2019b). However, Islamism’s rise against the regime through opposition groups like Liwa Suqour al-Sham, Ahrar ash-Sham and Jabaht al-Nusra offer continuity for the long war between Ba’athism and Islamism (Cepoi, 2013).

Conclusion

The imperial legacy leaves its mark differently for the Arab nationalist Ba’athists and the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood. For Arab nationalist ideologues such as Sati al-Husri and Michel Aflaq, the importing of Western intellectual thought and concepts such as nationalism and socialism was infused within an Arab cultural framing, leaving a synthesised ideology that sought to uplift Arabs into a bright future. For Islamists, rather than importing Western intellectual thought, the need to revitalise the region against Western encroachment meant an emulation of the Western scientific method and the use of reason, as well as the entrance into secular politics. Thus, in both cases there is a whip of external necessity; seen as regional intellectuals seeking to reinvigorate Arab societies to starve off Western encroachment into the region; and the privilege of historic backwardness; the attempt at emulating the Western experience by incorporating fundamental aspects of it, and infusing it in the Syrian context.

Although over the long war the two political organisations would drastically change in character from their outset, Arab Nationalism and Islamism, represented by the Ba’athists and the Muslim Brotherhood would continue to struggle against one another over the course of Syria’s modern political history. Right from the outset of Syria’s independence the two ideological camps struggled in the electoral arena, which once closed, transferred into armed struggle. Whilst the Ba’athist capture of the Syrian state ensured the death blow to the Islamists, the legacy of the conflict in many ways defines the parameters of Syria’s political arena today.

Bibliography

Abd-Allah, U.F. (1983). The Islamic Struggle in Syria. Berkely: Mizan Press.

Barr, J. (2011). A Line in the Sand: Britain, France and the Struggle for the Mastery of the Middle East. London: Simon & Schuster UK Ltd.

Cepoi, E. (2013). ‘The Rise of Islamism in Contemporary Syria: From Muslim Brotherhood to Salafi-Jihadi Rebels’, Romanian Political Science Review, 13(3), pp. 549-561. Available at: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=181912 (Accessed: 26 November 2021).

Commins, D.D. (1990). Islamic Reform: Politics and Social Change in Late Ottoman Syria. New York: Oxford University Press.

Conduit, D. (2016). ‘The Syrian Brotherhood and the Spectacle of Hama’, Middle East Journal, 70(2), pp. 211-226. doi: 10.3751/70.2.12

Conduit, D. (2019a). ‘Political Participation of Islamists in Syria: Examining the Syrian Muslim Brotherhoods Mid-Century Democratic Experiment’, Islam and Muslim-Christian Relations, 30(1), pp. 23-41. doi: 10.1080/09596410.2018.1546064

Conduit, D. (2019b). The Muslim Brotherhood in Syria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dawisha, A. (2016). Arab Nationalism In The Twentieth Century: From Triumph to Despair. (2nd ed). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Devlin, J. (1976). The Ba’th Party: A History from its Origins to 1966. Stanford: Hoover Institution Publications.

Hinnebusch, R. (1990). Authoritarian Power and State Formation in Ba’thist Syria. Boulder: Westview Press.

Hinnebusch, R. (2001). Syria: Revolution from Above. London: Routledge.

Kepel, G. (2002). Jihad: The Trial of Political Islam. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Marx, K. (2006). The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. Fairbanks: Project Gutenberg

Olson, R.W. (1982). The Ba’th and Syria, 1947 to 1982 The Evolution OF Ideology, Party And State: From The French Mandate to the Era of Hafiz al-Asad. Princeton: The Kingston Press.

Patel, A. (2013). The Arab Nahdah: The Making of the Intellectual and Humanist Movement. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Pierret, T. (2013). Religion and State in Syria: The Ulama from Coup to Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rosenberg, J. (2016b). ‘Uneven and Combined Development: ‘The International’ in Theory and History’, in Anievas, A. & Matin, K. (eds.) Historical Sociology and World History: Uneven and Combined Development over the Longue Dureé. London: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 17-31.

Stegagno, C. (2017). ‘Misil Aflaq’s Thought between Nationalism and Socialism’, Oriente Moderno, 97(1), pp. 154-176. doi: 10.1163/22138617-12340143

Teittelbaum, J. (2011). ‘The Muslim Brotherhood in Syria, 1945-1958: Founding, Social Origins, Ideology’, Middle East Journal, 65(2), pp. 213-233. doi: 10.3751/65.2.12

Tibi, B. (1997). Arab Nationalism: Between Islam and the Nation-State. (3rd ed). Basingstoke: Macmillan Press.

Trotsky, L. (2017). The History of the Russian Revolution. London: Penguin.

Van Dam, N. (1996). The Struggle for Power in Syria: Politics and Society under Asad and the Ba’th Party. (3rd ed). London: I.B. Tauris.