Hearing migrants’ powerful stories through art: What do we learn from it? – “Reflections of Displacement and Exile” Student Reflection

Safiye Coskun is a 3rd year student in Neuroscience at the University of St Andrews.

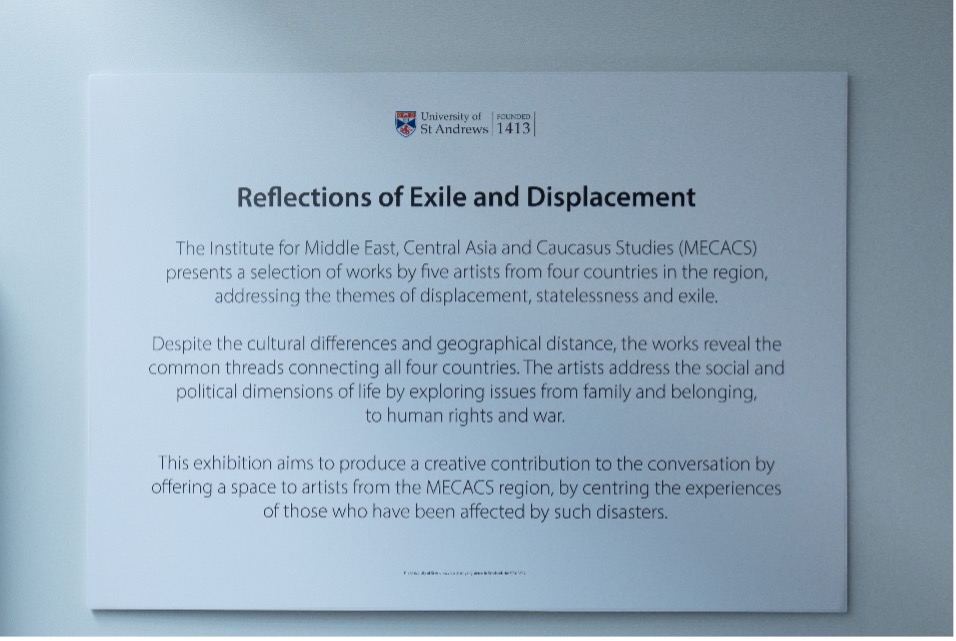

Being interested in migration from a neuropsychological perspective as a Neuroscience student, the recent MECACS (Middle East, Central Asia, and Caucasus Studies) art exhibition was a fantastic opportunity for me to discover the topics of displacement, immigration and their personal psychological effects reflected through art that enabled me to deepen my understanding of societal and legal aspects of the phenomena.

Participating in this project as a volunteer allowed me to have the perspective of a visitor as well as the running of the event. While I was making sure the venue I was allocated to was going smoothly, I had the chance to interact with students, local community members, and tourists from all around the world and hear what they think about this event’s themes. Like many of them, it was also my first time to see how artists of various places could use various methods and styles in the art to express their pre-migration experiences and post-migration conditions; which may include psychological, social, financial, or legal aspects. Some common examples may include long-term trauma and stress, reminiscence of their homeland after having experienced a risk of persecution, providing for their family’s needs, and improving the standards of life. As these were seen to be highlighted by different artists, it made me realise the common shared experience with forced migration, regardless of their homeplace or different experiences during the journey. Therefore, the stories and insights of those that encountered migration should be emphasised through unusual ways of expression and public education; that would allow for creating a welcoming environment and ease the adaptation process.

My favourite display was Father Hold My Hand by Ghafar; an abstract painting of a father, including cultural representations of his homeland; and a path that is blocked or unforeseen that would require unusual ways to find its way back onto the path. This could be due to the risk of persecution, war, discrimination or environmental. He also demonstrated a child that is dependent on the father as the canvas is physically attached to one of the fathers. The use of single colour to paint the child and the lack of patterns or motives catches attention that may indicate a lack of identity or memories attached to a certain place by the child; or an emphasis on innocence in the events they witness during their migration with their family. I found this piece truly relevant to myself, as someone having to relocate to the UK as a dependant to my father, with no sense of belonging to a particular place that creates confusion to self-identification while trying to figure out what comes next on the journey of resettlement. According to UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), the number of forcibly displacement people in the world has reached 108.9 million by the end of 2022. To help you imagine this population, there are only 14 countries with a population that exceeds this. This shows that this abstract painting is directly personal to millions of more people. As these statistics in the last years hit their highest-ever values every year; the lived experiences at distinct stages of the journey, the nature of mental, physical, and legal difficulties that create impacts should not go undetected while supporting for the best outcome.

As I came across Ghafar’s London exhibition named Afghani War Rugs Reimaginedduring the Refugee Week 2023; I had an invaluable moment to discuss his personal experience as a British Afghan. During this, I found out that his family had moved to the UK during his childhood, and the child in his painting the Father Hold My Hand was also a representation of his child image along with me and 43.3 million underage children that are over-represented in the statistics compared to the world population of children. As today’s children will mould tomorrow’s society, and the impacts of their lives would have clear effects on it, consciously or subconsciously. Just like how Ghafar mentioned to me that his expression of the stories of the Afghan diaspora occurred naturally as he proceeded with acrylic painting and handwoven rug. This leaves today’s society with a responsibility to make sure that tomorrow’s shapers continue to evolve positively towards social inclusion and make the world a better place than it has ever been.

Ghafar’s other work also made me see the common motives in his style, especially the cotton fringes. He uses it to refer to traditional Afghani rugs as a connotation to his homeland, or for a sense of cosiness. However, the uneven fringes on his piece of Father Hold My Hand made me ponder. Why would the fragment referring to a homeplace, or a sense of home be unequal? Could it be the disrupted connection with the physical or mental image of ‘the home’?

The settlement process for refugees takes time as it may require multiple countries and may have obstacles on the way to the destination; and may create difficulty to feel mentally safe and comfortable due to prolonged survival mode. This would have direct effects on self-identity and make confusion about how or where to call ‘the home.’ While this may have psychological implications, it also needs to be considered sociologically to allow for shared values and integration into the new place and is essential to bond different communities together for a sense of unity.

While art made by artists of migrant, asylum seeker or refugee background is displayed; it does not only show us their perspective but also allows for the rest of the society to acknowledge and show solidarity with the mental, financial, or legal frustrations refugees are likely to face. This is vital for creating social bonds and embeddedness into the agencies of socialisation. Just like how a single piece of art may discover so many distinct aspects of what means to face the risk of persecution and feel the need to find a safe place for a better future; it also indicates what can be done to support by the society for such a big-scale shared experience of exile. Unfortunately, the number of forcibly displaced people is only predicted to increase, and this indicates the state of urgency for cooperation from individual level socialisation to legal processes.

“It is the obligation of every person born in a safer room to open the door when someone in danger knocks.”- Dina Nayeri, The Guardian Interview

Sources

https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/04/dina-nayeri-ungrateful-refugee