MECACS Student Essay Prize – Honourable Mention (Sub-Honours)

Hoochang Yi is a second-year student in the School of Philosophy. This essay received an Honourable Mention in the Sub-Honours category of the 2023 MECACS student essay competition.

The role of the rule of law in the rise of contemporary homophobia in the Middle East

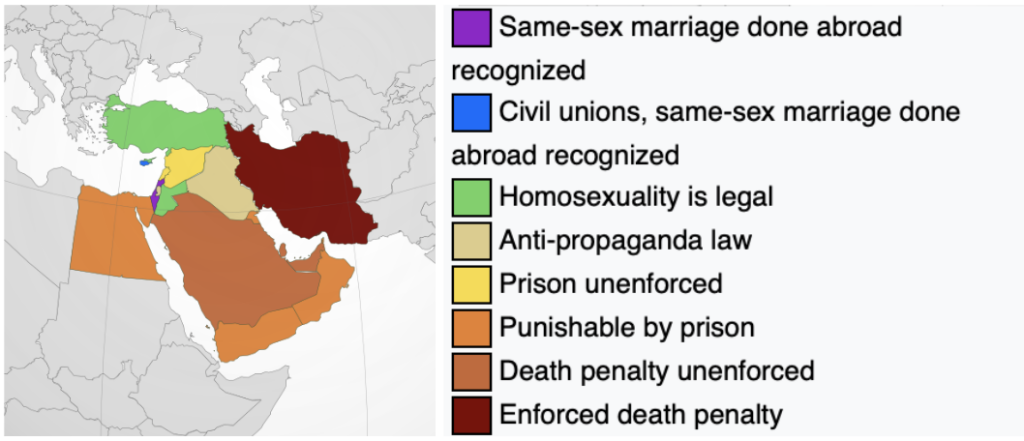

Currently, the jurisdictional rule of law in the Middle East is discriminatory against members of the Queer community, with Iran, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates prescribing the death penalty for consensual same-sex relations.[1] These jurisdictions are mainly based on Islamic rules of law, especially concerning the people of Lot.[2]Yet, the severity with which homosexuality is treated in the contemporary Arab world contrasts heavily with its rich sexual history, as AbuKhalil writes “[i]n the past, Muslims talked about sexuality without inhibitions or moral restraints.”[3] This will be the study into the role of the rule of law in changing the attitude towards non-heteronormativity in the Arab world. Yet to analyse this change through the medium of the rule of law, a definition is necessary. The primary conceptions of rules of law are jurisdictional and religious, yet for a sufficient study, an analysis of the societal normativity of the Arab world of the past and the present is necessary. These societal normativities not only, in a sense, lay down their own rules of law by creating a ‘norm,’ which through difference creates ‘deviance.’ They also come to structure the interpretation of religious rules of law, especially with which areas of scripture are most emphasised. This is important as contemporary jurisdictional rules of law against homosexuality are based upon religious norms. Thus, the ‘rule of law’ will include social conventions and normativity.

The social normative rules of law of the pre-19th century Arab world, which did not treat homosexuality with the severity that we see today, came to change as Arab scholars increasingly interacted with Western Orientalist scholarship. In turn, moulding the Arab intellectual elite into the Western dogma of medicalisation. This adoption of Western dogma was reinforced and encouraged by the anxiety that many Arab scholars felt in the wake of colonisation. Further, the Western discourse and categorization of homosexuality engulfed previous categories of homosexuality that existed in the Arab world, creating a new social normative rule of law that manufactured the category of ‘deviancy.’ Further, this new categorization of homosexuality came to be prescribed to those who still practised previous, local categories of homosexuality by the ‘Gay International’ and the Islamists.[4] Thus, prescribing to them ontological baggage that these local homosexuals had not known previously. By doing so, the tradition of unique homosexual identities came to be usurped and eroded by the Gay International and the Islamists, with the latter painting all homosexuals as deviants and as neo-colonial imports that put national sovereignty and culture at risk. Moreover, this new social norm structured the reading of religious texts by encouraging many scholars to emphasise certain passages of the Qu’ran and giving birth to new religious rules of law, which structured the contemporary jurisdictional rule of law of homophobia in the Middle East.

The discussion on the scriptural rule of law regarding homosexuality is initially necessary to understand how this rule of law came to be interpreted under different social normativities. In the Qu’ran the most explicit condemnation of homosexuality lies within the story of the people of Lot, where the town of Sodom and Gomorrah were destroyed by God due to their refusal to stop their homosexual practices.[5] Further condemnation of homosexuality can be found in the Prophet’s “Farewell Sermon” where he says “[w]hoever has intercourse with a woman and penetrates her rectum, or with a man, or with a boy, will appear on the Last Day stinking worse than a corpse.”[6] Thus, the religious rule of law regarding homosexuality in Islam seems to be quite straightforward, yet Islamic Queer history remains rich. This is not due to inconsistency in law and practice, but rather with the ambiguity of the punishment deemed necessary – this debate occupying two schools of thought (Hanafites and the Hanbalites) – and with the existence of various passages in scripture expressing the beauty of male Catamites and young boys.[7] This ambiguity being exploited by many, such as Abu Nuwas – who wrote extensive erotic poetry on young boys. Within this scriptural ambiguity, a unique sexual identity came to be formed where there was a distinction between the penetrator and the penetrated; an adult man could not retain his honour if he remained an ‘ubnah’ (the passive actor in homosexual sex), but where the penetrator could retain his dignity. This social norm is coming to change with its interaction with Western scholarship. [8]

The unique Arab sexual norm was witnessed with shock by Orientalists, such as James Silk Buckingham. Writing in 1827, Buckingham noted in his Travels in Mesopotamia,

I have felt it my duty, as an observer of human nature to record, …, this mark of profligacy, to which the classical scholar will readily remember parallels in ancient manners, but which among the moderns has been thought by many to be nowhere openly tolerated.[9]

Buckingham was describing the exotic boy dancers who wore “silver ornaments peculiar to female dancers,” as the “depravity not to be named.”[10] Orientalist literature, which degrades and ‘denudes’ the culture of study, came to be consumed by the intellectual elites of the Arab world during the 19th century.[11] The introduction of the printing press created a new literate public which deemed the previous form of local academic practices as being too reliant on manuscripts and came to unquestioningly adopt “the epistemology by which Europeans came to judge civilisations and cultures along the vector of something called ‘sex.’”[12] The engagement with Orientalist literature was fueled to a significant extent by the anxiety that the Arab world felt in the wake of European colonisation and global dominance. For instance, one Arab commentator wrote in 1906 “[w]hy have Muslims regressed and why have others progressed?”[13]With these new tools of internalised Western concepts, Arab intellectuals sought to answer the question of why the Arab world lacked ‘modernity,’ inventing new words to aid in this project – such as tammaddun (civilisation), inhilal (degeneration) and turath (heritage).[14] This project accusing the non-heteronormative sexual norms of the Arab world as a key reason for its ’degeneracy.’

The anxiety of the Arab scholars in trying to assimilate their past into the modern project is seen in their treatment of the Abbasid poet, Abu Nuwas (756- 814), which Joseph, A. Massad explores in detail. The beginning of the 20th century saw studies into Abu Nuwas that lacked hostility against his ‘deviant’ lifestyle, with Taha Husayn placing the artistic importance of the Ghazal poetry (poetry that is often erotic) of Abu Nuwas over the contemporary moral stances.[15]However, his effort at placing the origin of Ghazal poetry and the sexual openness of the Arab world on the Persians preluded and contributed to the subsequent discussions on addressing the tensions between the past and the modern Arab world, by surgically discounting aspects as ‘non-Arab.’[16] Muhammad al-Nuwayhi psychoanalyses Abu Nuwas and places his sexual deviance on the fact that his father died when he was young with his mother marrying another man.[17]He then implements a social Darwinian analysis of Abu Nuwas’ contemporary society, arguing that the abundance of sexual ‘deviance’ was symptomatic of the decline of the Abbasid era. With these examples, one can see the adoption of Western methodology and conceptualization in Arab academia to analyse their history The discourse of the ‘foreign’ Persians introducing ‘degeneracy’ into the Arab world subtly implies the ontological reality of the ‘Arab’ as an identity, which is reminiscent of primordialism of Nationalist Europe, whilst the description of the Abbasid sexual norms as ‘deviant’ implies the universality of modern, Victorian sexual morality. Thus, the anxiety of the Arab academia in dealing with their Queer history arose from their interactions with Western orientalist scholarship. With these interactions, the Arab literati adopted Victorian sexual normative rules of law and contemporary European obsession with the question of modernity. Through this medium the Arab literati judged their sexual norms, in history and contemporary Arab society, condemning them as deviant and degenerate. It should also be pointed out that these homophobic discourses were actualized into legislation. Whether it be the maintaining of imported homophobic legislation of the Napoleonic code or the legislative attempt at cleansing the literature around Abu Nuwas’ queer life, exemplified by the banning of Ibn Manzur’s 13th-century book on Abu Nuwas’ life.[18]

An interesting debate in the historiography of homosexuality in the Arab world is whether the concept and categorization of homosexuality existed before the extensive interaction with the West. Massad argues in a Foucauldian line, maintaining that though there were ‘homosexual’ acts, there was no ‘homosexual’ identity to categorise these acts within. He argues that the Western obsession with Human rights and their imposition of gay rights on the Arab world strengthened the discourse of homophobia in the Arab world.[19] In a time of post-colonialism and fear against neo-Colonialism, with this fear often being allegorized through the homosexual rape, and emasculation, of the Arab world, it is clear why the Western emphasis on Gay rights was not received happily in the Arab world.[20] This was worsened as the ‘Gay international,’ as Massad calls it, prescribed the homosexual identity to anyone who practised ‘homosexual’ acts, ontologically placing them in direct opposition to Arab nationalism and culture. Thus, the social rule of the law of homophobia came to adopt a nationalist, anti-colonialist message which connected itself to Arab culture and a struggle against Western imposition.

However, Stephen O. Murray and Will Ruscoe maintain the existence of homosexuality as a concept before the Western medicalisation of homosexuality, by citing various words that were used to describe people with homosexual tendencies (obnai, fā’īl, ghulām) and citing Ibn Sina who wrote of Ubnah as a state of being; with Murray arguing that attempts at denying this can be categorised as a Western ‘will not to know’ that such categories existed before Western medicalisation.[21] Further, Katerina Dalacoura argues that Massad, by denying the existence of homosexuality in the Arab world, not only unjustifiably detaches Arab history from European history, but he also denies the homosexuals as not of the Arab world but as a Western import, in turn denying their political legitimacy.[22] Thus, Massad’s post-colonial analysis seems to commit the same methodological flaws of the Modernist in the Arab world, dismissing evidence and certain sources that did not fit into the post-colonial narrative.

However, there is value in Massad’s critique of the Gay International’s incitement to discourse. Though it may be true homosexuality existed as an identity before the advent of Western medicalization in the Arab world, egalitarian homosexuality did not.[23] The modern form of egalitarian homosexuality with a hyper fixation on the ‘Rights’ of the Gay individual did not exist in the past of the Arab world and this ‘Gay’ is what Massad is referring to in talking about the ‘Gay international.’ Arab homosexuality always had a strong emphasis on the distinction between the penetrator and the penetratee, with the penetrator maintaining their masculinity and dignity, and the penetratee being “considered pathological.”[24] As Wafer puts it “a man’s masculinity is compromised by taking the passive role in sexual relations.”[25] These Arab homosexualities, where there was a clear status distinction between the penetrator and the pentratee, came to be engulfed by the Western egalitarian homosexuality that identified these different instances as one and the same. This prescription collapsed the status distinction, reducing all those involved to the status of the ubnah and robbing masculinity from the active role. This new form of homosexuality was forcefully encouraged and prescribed to the Arab world by the Gay International. The Gay International collapses all instances of queerness into the rigid category of the ‘Homosexual,’ with this identification being supported by the Islamists of the Arab world. The Islamists utilized this Western imposition and portrayed it as another form of colonialism which threatened their culture and sovereignty, thus portraying homophobia as a symbol of nationalism and anti-colonialism. Thus, the societal rule of law of homophobia in the Arab world was strengthened as homophobia came to represent a form of cultural defence against Western cultural aggression.

The rule of law concerning male homosexuality in the Arab world shifted into intolerance through their interaction with Western scholarship and global politics. The anxiety at ‘falling behind the West’ drove the Arab intellectuals of the 19thand early 20th century to condemn the queer aspects of Arab history as ‘deviant’ and ‘decadent’ as they came to adopt European societal rules of law. The sexual deviancy in the Arab world, which was ridiculed and judged with disgust by the Orientalists, was seen as one of the key components in the ‘decay’ of the Arab region and an explanation for why the Arab world had fallen behind in the natural progression of society. The homophobia in this new societal rule of law was strengthened in the post-Colonial era as the Gay International forcefully identified local queer customs along the lines of Western homosexuality and urged their ‘liberation,’ from colonial-era societal rules of law, in accordance with Western queer liberation. This action tried to fit the Arab world into the societal progression of the West, mimicking the Orientalist tradition. By doing so, they strengthened the societal rule of law of homophobia through nationalism, culture and anti-colonialism. This new societal rule of law came to structure the interpretation of religious rules of law coming to emphasise their homophobic elements which came to be actualized into legislative, homophobic rules of law.

Bibliography

Manuscripts

Qu’ran

Printed Primary Sources

Buckingham, James Silk, Travels in Mesopotamia, (Cambridge, 827/2011)

Secondary Sources

AbuKhalil, As’ad, A Note on the Study of Homosexuality in the Arab/Islamic Civilization, The Arab Studies Journal, 1: 2, (Fall 1993)

Dalacoura, Katerina, Homosexuality as cultural battleground in the Middle East: culture and postcolonial international theory, Third World Quarterly, 35: 7. (2014)

Kligerman , Nicole, Homosexuality in Islam: A Difficult Paradox, Macalester Islamic Journal, 2: 3 (3-28-2007)

Pratt, Nicola, The Queen Boat Case in Egypt: Sexuality, National Security and State Sovereignty, Review of International Studies, 33: 1, (2007), pp. 129-144

Massad, Joseph A., Desiring Arabs (Chicago, 2007),

Murray, Stephen O., The Will not to Know, in Stephen O. Murray and Will Ruscoe (eds), Islamic Homosexualities (New York, 1997)

Murray, Stephen O., Ruscoe, Will, Conclusion, in Stephen O. Murray and Will Ruscoe (eds), Islamic Homosexualities

Ruscoe, Murray, Introduction, in Stephen O. Murray and Will Ruscoe (eds), Islamic Homosexualities (New York, 1997)

Said, Edward, Orientalism, (London, 1978)

Schmidtke, Sabine, Homoeroticism and Homosexuality in Islam: A Review Article, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 62: 2, (1999), pp. 260-266.

Wafer, Jim ‘Muhammad and Male Homosexuality’, in Stephen O. Murray and Will Ruscoe (eds), Islamic Homosexualities (New York, 1997)

Internet Sources

Loft, Phillip, Robinson, Timothy, Curtis, John, Mills, Claire, Dickson, Anna, Rajendralal, Reshma, ‘LGBT+ rights and issues in the Middle East’, House of Commons Library, London, 9th February 2022, < https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9457/> [18th June 2023].

Long, Scott, ‘The Trials of Culture,’ Middle East Research and Information Project: Critical Coverage of the Middle East Since 1971, Spring 2004, < https://merip.org/2004/03/the-trials-of-culture/> [Accessed 25 June 2023].

[1] Phillip Loft, Timothy Robinson, John Curtis, Claire Mills, Anna Dickson, Reshma Rajendralal, ‘LGBT+ rights and issues in the Middle East’, House of Commons Library, London, 9th February 2022, < https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9457/> [18th June 2023].

[2] Qu’ran 26:161.

[3] As’ad AbuKhalil, A Note on the Study of Homosexuality in the Arab/Islamic Civilization, The Arab Studies Journal, 1: 2, (Fall 1993), pp. 32-34.

[4] Joseph A. Massad, Desiring Arabs (Chicago, 2007).

[5] Qu’ran 11:82

[6] Nicole Kligerman, Homosexuality in Islam: A Difficult Paradox, Macalester Islamic Journal, 2: 3 (3-28-2007), p. 3

[7] Jim Wafer, ‘Muhammad and Male Homosexuality’, in Stephen O. Murray and Will Ruscoe (eds), Islamic Homosexualities (New York, 1997), pp. 89-90.

[8] Massad, Desiring Arabs, p. 94

Stephen O. Murray, Will Ruscoe, Conclusion, in Stephen O. Murray and Will Ruscoe (eds), Islamic Homosexualities (New York, 1997), p. 306

Stephen O. Murray, The Will not to Know, in Stephen O. Murray and Will Ruscoe (eds), Islamic Homosexualities (New York, 1997), p. 21

[9] James Silk Buckingham, Travels in Mesopotamia, (Cambridge, 827/2011), p.168.

[10] Ibid., pp. 166-167.

[11] Edward Said, Orientalism, (London, 1978), p. 108.

[12] Massad, Desiring Arabs, p. 6

[13] Ibid., p. 16

[14] Ibid., p. 53

[15] Ibid., p. 62

[16] Ibid., p. 75

[17] Ibid., p. 85

[18] Katerina Dalacoura, Homosexuality as cultural battleground in the Middle East: culture and postcolonial international theory, Third World Quarterly, 35: 7. (2014) pp. 1290-1306.

Massad, Desiring Arabs, p. 81

[19] Massad, Desiring Arabs, p. 194-195

[20] Ibid. 380

[21] Murray, The Will not to Know, p. 29.

[22] Dalacoura, Homosexuality as cultural battleground in the Middle East: Culture and postcolonial international theory, pp. 9-13

[23] Ruscoe, Murray, Introduction, in Stephen O. Murray and Will Ruscoe (eds), Islamic Homosexualities (New York, 1997), p. 4

[24] Kligerman, Homosexuality in Islam: A Difficult Paradox, p. 2

[25] Wafer, ‘Muhammad and Male Homosexuality,’ p.91