MECACS Student Essay Prize – Honours Category Winner

Stuart Ramsey is a 4th year student in the School of History. This essay was awarded first prize in the Honours category of the 2023 MECACS Student Essay competition.

The Assise sur la Ligece: a reevaluation of the actions of the Outremer barons during the thirteenth century

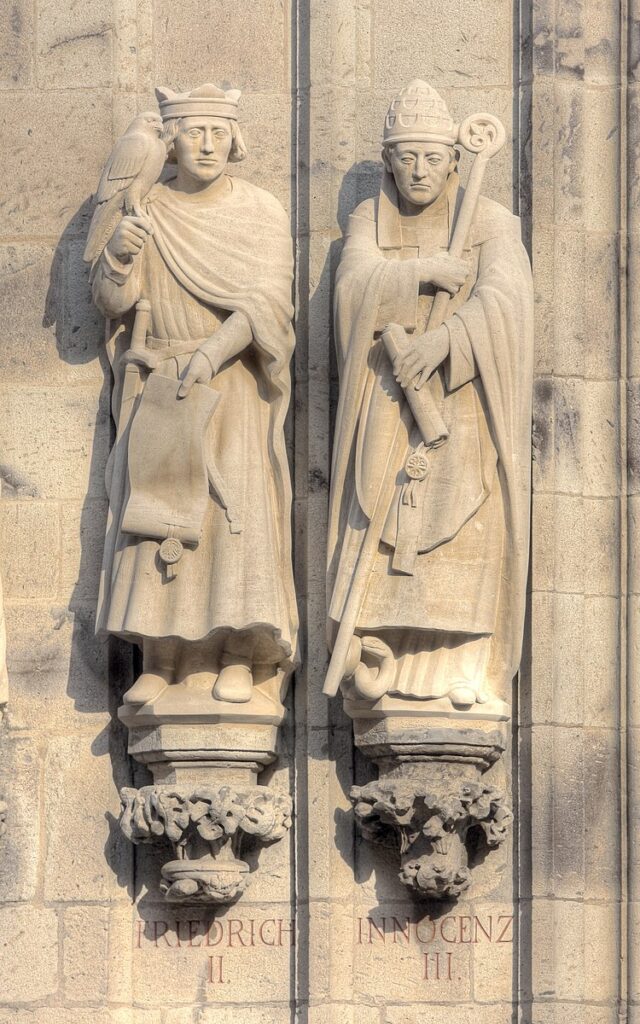

In the autumn of 1228, Emperor Frederick II of the Holy Roman Empire arrived on the Levantine coast to conduct his long-anticipated crusade. He came not merely as another crusader but as the regent of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the suzerain of the Kingdom of Cyprus.[1] Not long after his arrival, problems emerged between him and the barons of the Kingdom of Jerusalem; when he returned to Europe, he left behind a fractured kingdom that did not reunify until 1243. Historians of the crusader states have often related this conflict as one in which the barons defended the kingdom’s constitutionalist state against the centralising forces of the emperor. This has helped to cement the view that the baronage were exceedingly concerned with preserving the old customary law of the kingdom. [2] One eminent historian imparted to John d’Ibelin of Beirut, the leader of the resistance, the description of “defender of baronial liberties against imperial aggression.”[3] The writings of the Latin jurists helped to impart this view; they claimed that the barons were justified in their resistance to Frederick II because of the principles derived from a twelfth century law called the Assise sur la Ligece. It is the goal of this essay to challenge the legal reputation of the barons as this helps to shroud their more opportunistic motives. I will initially argue that the actions taken by the barons in the thirteenth century had no prior legal precedent, contrary to what the jurists claimed. I will then show that when the barons created the Commune of Acre in their efforts to oppose the emperor, they went beyond the legal justifications they purported to operate under. In doing so, I hope to demonstrate that the victory of the barons over the imperial forces should not be considered an extraordinary legal triumph, but as merely just another episode of mediaeval power politics.

The Assise sur la Ligece was originally designed to empower the monarchy. According to the Latin jurists, the basis for the assise came from a dispute between King Amalric and one of his tenant-in-chiefs, Gerard of Sidon. In 1166, Gerard had disseized one of his own vassals without first acquiring the judgement of his seigneurial court. Amalric then intervened on behalf of the rear-vassal and restored his fief to him.[4] The king then legislated that every vassal of the realm was to pay homage directly to the king, establishing a direct connection between the rear-vassals and the king.[5]Under this law, these vassals were afforded the ability to appeal to their king directly if denied justice by their own lords.[6] In addition, the law enumerated that a vassal was also permitted to summon his lord to hold court, and if his lord failed to do so, could withdraw his service and convince his peers to do likewise. If these efforts were in vain, necessary force was thus justified.[7]

In 1197, the barons of the kingdom tried to expand the scope of the assise to apply to the monarch. After a failed assassination attempt, King Aimery accused his vassal Ralph of Tiberias of complicity in the crime and subsequently exiled him from the kingdom without trial.[8] In his defence, Ralph invoked the assise and argued that his exile was illegal. He then persuaded his peers to withdraw their services from the king. Despite this, he still departed from the kingdom, and the other vassals eventually resubmitted their services; Ralph was only able to return to the kingdom until after the king’s death.[9] This apparent failure on the part of the barons to compel the king to their demands would suggest that the assise would therefore not be expanded to apply to the king; however, the jurists of the thirteenth century claimed it had successfully done so. Philip of Novara in his Le Livre de Forme de Plait (ca. 1250s) wrote how Ralph’s resistance to the king was a justified use of the “aspect of the assise that was made after the conflict between King Amaury and my lord Gerard of Sidon.”[10] He argued that the widened applicability of the assise provided the barons with a legal means of resisting arbitrary acts by the monarch against his vassals.

How could the jurists claim that the kingdom adopted the barons’ interpretation of the assise after King Aimery had so clearly triumphed in his dispute with Ralph of Tiberias? This development can be explained by considering the backgrounds of the principal jurists, Philip of Novara and John of Jaffa; they were both partisans of the baronial cause against the emperor in the thirteenth century and were writing well after the events of the twelfth century. It is likely that they deliberately misinterpreted this event to provide a historical precedent to help justify their contemporary cause against the emperor.[11] Regardless of their arguments, the assise was most likely not considered to apply to the king at this point. This establishes the important idea that the resistance of the barons to the emperor was not, as was previously assumed by historians, relying on established precedent but was in fact an innovation of the legal principles of the Assise sur la Ligece. This means that the expansion of the assise must have taken place during the next time it was invoked, which was during the conflict with the emperor.

There were two instances in early 1229 during the crusade of Frederick II in which the barons successfully utilised the assise. The emperor tried to deprive John of Beirut, John of Caesarea, John of Jaffa, Rohard of Haifa, Philip L’Asne, and John Moriau of their fiefs in the city of Acre without trial. Like Ralph of Tiberias in 1197, these men invoked the Assise sur la Ligece and appealed to their peers for aid; unlike Ralph, however, they used force of arms to regain their fiefs when they were accorded no justice by Frederick.[12] In another instance, the emperor tried to grant the city of Toron to the Teutonic Order, but this was disputed by Alice of Armenia based on her hereditary right to the fief. A meeting of the vassals in the High Court of Jerusalem decided in favour of Alice, but the emperor forbade them from granting her the fief. The vassals then withdrew their services from the emperor en masse until he relented.[13] Historians claim that the barons won in these instances because Frederick was eager to avoid serious conflict so he could sooner return to the West where the pope was invading his territories in Italy.[14] Regardless, these two instances should be considered as successful implementations of the assise against the king using the proper procedures described by the Latin jurists.

The barons again appealed to the assise in 1231 after Frederick II ordered his marshal Richard Filangieri to besiege John d’Ibelin’s fief of Beirut. The aggrieved lord recruited other barons to his cause; this time, however, they failed to compel their liege to capitulate through force.[15] The kingdom was then split between the two parties for the next decade; Filangieri based in Tyre and the barons in Acre. One might argue that the earlier two episodes with the emperor had already established a precedent that the assise now applied to the king, whereas the barons were simply referring to this precedent when justifying their actions concerning Beirut. However, since these events occurred within a few years of each other, and that they were made against the same person, we ought to judge these together, not as separate cases.

It was during this impasse between the two parties that the barons established the Commune of Acre, electing John d’Ibelin as its first mayor.[16] This body was formed for the mutual defence of the barons against the emperor. It originated from an earlier organisation, the Confraternity of St Andrew, a sworn association of barons, knights, and burgesses constituted under the auspices of Baldwin IV and Henry of Champagne.[17] It possessed similarities to the communes in the West in that it had its own hierarchy of officers elected annually and used a bell to summon their meetings.[18] Jonathan Riley-Smith claimed that, despite these similarities, the Commune of Acre was unlike those in the West in that held neither legal jurisdiction over the city nor the kingdom.[19] He based this conclusion on the evidence that the previous municipal and state officials were still functioning during the period of the commune. He suggested that instead the commune’s role was purely to provide an alternative means of resistance to the emperor after the barons had failed to resolve the conflict through the methods provided by the Assise sur la Ligece.[20] Riley-Smith is right to stress the importance of resistance as a motivation for the establishment of the commune; however, he is incorrect in his estimation that it was its sole function. We can conclude that the commune must have held some greater form of legal standing based on its role in the accession of Queen Alice to the regency of the kingdom in 1243. Marsiglio Georgio, the bailii of the Venetian commune in Acre, wrote that after Alice made a petition for the throne, “the houses which are under rule [i.e., monastic houses], the commune of the city of Acre, the communes of the Venetians and the Genoese,” as well as the prelates and barons of the kingdom, took “counsel together, seeing that what the queen asked was just, consented to her petition as a just one.”[21] Each of these parties had formal roles within the kingdom; it would be peculiar if the commune was also consulted if it did not have a similar authority to the other entities. Assuming this, it would indicate that the commune would have held some form of institutional role within the kingdom, or at the very least some legal authority on par with the other groups.

Defining the nature of the Commune of Acre is important because if we should consider it as a legal government entity within the kingdom, combined with the fact that it was instituted by the barons to help them oppose the forces of the emperor, we should then evaluate it within the boundaries of the Assise sur la Ligece, as this was explicitly the barons’ legal justification for their whole enterprise against the emperor.[22] The assise permits a vassal, who was unlawfully dispossessed of a fief by their lord and denied the chance to defend their rights in court, to recruit other vassals to aid in his opposition, be it armed resistance or simply withdrawing their services. The law, however, does not permit vassals to recruit private burgesses to their cause or create new legal entities. The feudal oaths made by the vassals with their king entitle them to the privileges of this law; the legal relationship of the burgesses with the king, however, is not the same as the one he shares with his vassals. Therefore, we should view the establishment of the commune by the barons as exceeding the limits of the law as understood by the assise. One historian has suggested that perhaps the assise also applied to those few burgesses who held fiefs from the king; whether this was the case matters little here.[23] As Peter Edbury has noted, the commune participated in and led popular revolts against the forces of the emperor; its membership also reported to be open to any freeman.[24] This implied that its membership extended far beyond that of a few high-ranking burgesses. The mass of Frankish subjects in Acre who might have joined the commune could not all have possibly held fiefs on behalf of the king. Inciting a mass movement against the emperor clearly went beyond the principles of the assise; therefore, the barons’ establishment of the Commune of Acre should be considered illegal.

As we discussed prior, the barons of the thirteenth century were not supported by precedent when they invoked the Assise sur la Ligece against the emperor; we should therefore interpret their efforts as an attempt to expand the scope of the law. In addition, since the commune was instituted to help resist the emperor, we should consider its legality under the auspices of the assise. If we were to imagine ourselves as hypothetical judges tasked with weighing the merits of the barons’ case, we should decide against them based on the illegality of their establishment of the commune. Unfortunately, this was not how legal precedent was determined in this period. Since the barons won their war against the emperor and gained control over the kingdom for themselves, their interpretation became law. Is this fair? The classic argument of “might makes right” would suggest so; however, it is not within the scope of this paper, nor the abilities of the author, to make any educated judgements on political philosophy. Instead, what we should conclude is that historians of the Crusades need to reevaluate their portrayal of these barons. No longer should they be characterised by noble respect for the rule of law; their concern for the law consisted of justifying their illegal seizure of power from the rightful ruler of Jerusalem. In this sense, they ought to be regarded as no different from other groups in the quest for power.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

‘Account of Marsiglio Georgio, the Venetian bailli [October 1243]’, in Appendix IV of John L La

Monte’s translation of Philip of Novara’s The Wars of Frederick II against the Ibelins in Syria and Cyprus (New York, 1936), pp. 205-7.

Philip of Novara, Le Livre de Forme de Plait, trans. and ed. Peter W. Edbury (Nicosia, 2009).

–––. The Wars of Frederick II against the Ibelins in Syria and Cyprus, trans. and ed. John L La

Monte (New York, 1936)

Secondary Sources

Edbury, Peter W., John of Ibelin and the Kingdom of Jerusalem (Woodbridge, 1997).

La Monte, John L., ‘Introduction’, in his translation of Philip of Novara’s The Wars of Frederick

II against the Ibelins in Syria and Cyprus (New York, 1936).

–––. ‘John d’Ibelin: the Old Lord of Beirut, 1177-1236’, Byzantion 12: 1/2 (1937),

pp. 417-448.

–––. ‘The Communal Movement in Syria in the Thirteenth Century’ in C.H.

Taylor (ed.), Anniversary essays in mediaeval history presented on his completion of forty years of teaching. By students of Charles Homer Haskins (Boston, 1929), pp. 117-131.

Loud, G.A., ‘The Assise sur la Ligece and Ralph of Tiberias’, in Peter W. Edbury (ed.), Crusade

and Settlement. Papers read at the First Conference of the Society for the Study of the Crusades and the Latin East and presented to R.C. Smail (Cardiff, 1985), pp. 204-213.

Mayer, Hans Eberhard, ‘On the Beginnings of the Communal Movement in the Holy Land: the

Commune of Tyre’, Traditio 24: 1 (1968), pp. 443-457.

Prawer, Joshua, Crusader Institutions (Oxford, 1980).

Riley-Smith, Jonathan, ‘The Assise de Sur La Ligece and the Commune of Acre’, Traditio 27: 1

(1971), pp. 179-204.

–––. The Feudal Nobility and the Kingdom of Jerusalem, 1174-1277 (London, 1973).

[1] Frederick was regent of his infant son King Conrad, his child with the late Isabella II of Jerusalem; Cyprus was an imperial fief.

[2] Hans Eberhard Mayer, ‘On the Beginnings of the Communal Movement in the Holy Land: The Commune of Tyre’, Traditio 24: 1 (1968), p. 444; Joshua Prawer, Crusader Institutions (Oxford, 1980), pp. 46-9.

[3] John L. La Monte, ‘John d’Ibelin: the Old Lord of Beirut, 1177-1236’, Byzantion 12: 1/2 (1937), p. 430.

[4] G.A. Loud, The Assise sur la Ligece and Ralph of Tiberias’, in Peter W. Edbury (ed.), Crusade and Settlement (Cardiff, 1985), pp. 204-5.

[5] Johnathan Riley-Smith ‘The Assise de Sur La Ligece and the Commune of Acre’, Traditio 27: 1 (1971), p. 180.

[6] Loud, ‘Ralph of Tiberias’, p. 205.

[7] Riley-Smith, ‘Assise’, pp.180-3.

[8] Ibid., p. 189.

[9] Ibid., pp. 184-191.

[10] Philip of Novara, Le Livre de Forme de Plait, trans. and ed. Peter W. Edbury (Nicosia, 2009), pp. 255-6.

[11] G.A. Loud, ‘Ralph of Tiberias’, pp. 204-13.

[12] Jonathan Riley-Smith, The Feudal Nobility and the Kingdom of Jerusalem, 1174-1277 (London, 1973), pp. 170-1.

[13] Ibid., pp. 171-2.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Riley-Smith, Feudal, pp. 175-8.

[16] Peter W. Edbury John of Ibelin and the Kingdom of Jerusalem (Woodbridge, 1997) pp. 24-58; John L. La Monte ‘Introduction’ in The Wars of Frederick II against the Ibelins in Syria and Cyprus (New York, 1936) pp. 21-59.

[17] Riley-Smith, ‘Assise’ p. 195.

[18] Ibid., p. 197.

[19] For alternative interpretations, see: John L. La Monte ‘The Communal Movement in Syria in the Thirteenth Century’ in C.H. Taylor (ed.), Anniversary essays (Boston, 1929), (civic function); Prawer, Crusader, pp. 45-68 (state function); (mixed), Mayer, ‘Beginnings’, pp. 443-6.

[20] Riley-Smith, ‘Assise’, pp. 197-8.

[21] ‘Account of Marsiglio Georgio, the Venetian bailli [October 1243]’, in John L La Monte, Wars, p. 206.

[22] Philip of Novara, Le Livre, pp. 255-6.

[23] Riley-Smith, ‘Assise’, p. 181.

[24] Edbury, John of Ibelin, p. 53; Riley-Smith, ‘Assise’, p. 196.