Lasting Legacies of Oman’s Anticolonial Revolution – a Seminar with Alice Wilson

This blog post was written by Alice Wilson, a Senior Lecturer in Anthropology at the University of Sussex. Her research focuses on transformations in the relationship between governing authorities and governed constituencies in revolutions and liberation movements in Southwest Asia and North Africa, in particular in Western Sahara and Oman. She is the author of Afterlives of Revolution: Everyday Counterhistories in Southern Oman (Stanford, 2023) and Sovereignty in Exile: a Saharan Liberation Movement Governs (Pennsylvania, 2016). Alice Wilson presented her most recent book at a MECACS seminar on the 23rd January, 2024, hosted by Dr Hsinyen Lai.

How does a revolution survive repression? And how do the legacies of revolutionary ideas, values, and relationships that survive defeat invite new interpretations of revolution, counterinsurgency, and their aftermaths?

These questions hang over disappointed revolutionaries in South-West Asia and North Africa (SWANA) in the wake of the Arab Uprisings, and other recent mass protests, that did not achieve the political and economic transformations for which participants strove.

These recent revolutions have nevertheless radically changed many people’s sense of themselves and their relations with others. Turning to the region’s anticolonial revolutionaries of the 1960s and 1970s suggests even longer-term possibilities: the enduring impacts of revolutionary values beyond defeat and repression. These lasting legacies of revolution, and their implications, are the subject of my latest book, Afterlives of Revolution: Everyday Counterhistories in Southern Oman.

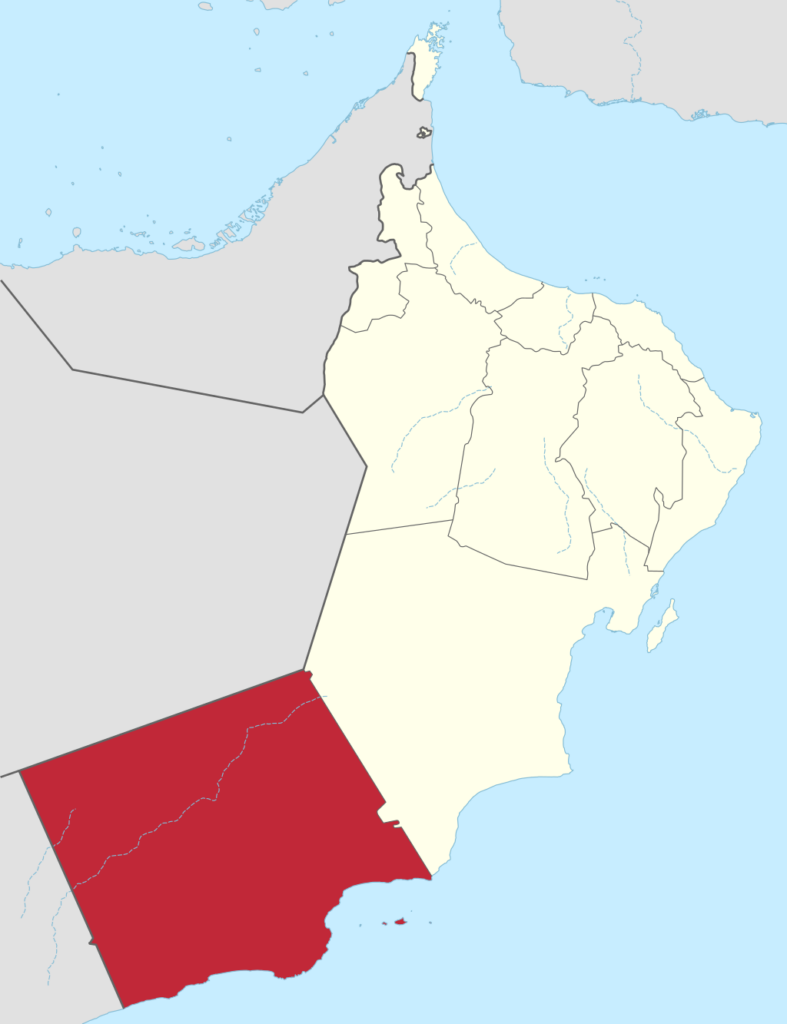

Source: ‘Dhofar in Oman’, by Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0 DEED

The southern governorate of today’s Oman is Dhufar, a part of Arabia once famous for its frankincense. From the late 19th century, the Muscat-based, British-backed al-Busaid dynasty of Sultans claimed the region. But Dhufaris chafed under their harsh rule, and in 1965 founded an anticolonial liberation front that fought for emancipation from the British-backed Sultans, while striving to promote social emancipation and egalitarianism. From 1965 to 1976, Dhufar’s anticolonial revolutionaries, and their projects for social transformation, brought the region new renown.

The liberation front faced a British-led, and increasingly internationalized counterinsurgency. By 1976, this campaign defeated the liberation movement. Thereafter, Oman’s postwar government expunged the revolution, as well as government violence to repress it, from official history.

Britain had initially tried to keep its participation in the conflict secret, in line with officially denying its colonial relationship with Oman. But in the decades after the war’s end in 1976, some veterans of the counterinsurgency, and some scholars, eulogized a “model” campaign. They praised the alleged avoidance of violence against civilians, and the use of welfare provisions to win “hearts and minds”. Such accounts portrayed the revolution as unpopular among Dhufaris, and a threat to the nation.

Many, however, have refuted the erasure and dismissal of the revolution, as well as the eulogization of the counterinsurgency. Omanis publishing outside government censorship, such as writer and activist Said Hashemi, researcher Mona Jabob, and novelists Ahmed al-Zubaidi and Bushra Khalfan, reclaim the revolution as a significant period of national history and identity. Meanwhile, historian Abdel Razzaq Takriti has retrieved the agency of Oman’s revolutionaries and their shaping of the course of history.

Moreover, the counterinsurgency’s extensive violence against Dhufaris – air strikes, food and water blockades, mass forced displacement, and the destruction of the subsistence economy – bely claims of minimal violence affecting civilians. Indeed, the reliance on such violence in Dhufar, and in other counterinsurgency wars of liberal governments, leads political scientist Jaqueline Hazelton to argue that, despite claims to the contrary, violence against civilians is necessary for, rather than detrimental to, the military success of these campaigns.

These debates, with their focus on revisiting events during the conflict, lead me to make two interventions in Afterlives of Revolution.

Source: Stanford University Press

First, I take up an ethnographic lens, that situates experiences within social and historical contexts, to revisit events during the revolution and counterinsurgency. For instance, such a lens questions dismissive portrayals of the revolution as “red terror”, by contextualizing intra-revolutionary violence within revolutionary and colonial transformations of indigenous categories of political violence.

Second, I extend the time period for rethinking revolution to include afterlives – the lasting legacies of revolution that survive beyond defeat and repression. During my fieldwork in Dhufar in 2015, four decades after the revolution’s defeat, I had the privilege of learning how some veteran militants reproduce revolutionary values of social egalitarianism along lines of gender, social status, tribe and racialized identities.

The book thus brings into conversation a historical ethnography of revolutionary social change and counterinsurgency with a fieldwork-based ethnography of former revolutionaries’ postwar lives. This has entailed many methodological and ethical challenges – most of all participants’ well-being amid ongoing surveillance and repression. Navigating intersecting constraints and possibilities, my book explores how, to different degrees that reflect their own positionalities and relative privilege or marginalization, some former militants create afterlives of revolution: in their kinship practices and everyday socializing, and when they unofficially commemorate the revolution.

These afterlives, I argue, invite reconsideration of revolution, counterinsurgency, and their aftermaths. The survival of revolutionary values prompts reflection on the “messy” qualities of revolutionary social change that may diverge from neat scripts of “progress”, but nevertheless lay foundations for legacies to persist. Afterlives of revolution also foreground the extended times, places and impacts of revolutionary agency, such as when former militants shape postwar social and spatial transformations, despite ongoing counterinsurgency agendas. Moreover, afterlives of revolution suggest how counterinsurgency violence and patronage fall short of erasing long-term engagement with revolutionary values.

In the light of revolution’s lasting legacies in Oman, the erasure and dismissal of revolution and the eulogization of counterinsurgency emerge as condemnations of the agency and resistance of colonized subjects, and the legitimization of colonial violence. I argue that by calling out these colonial narratives, and retrieving the agencies that they seek to dismiss, afterlives contribute to “an effort toward decolonizing narratives of revolution and counterinsurgency”.

In SWANA today, as counterrevolutionary governments vilify the Arab Uprisings, and amid the devastation of war for Palestinian civilians, revolutionary legacies in Oman and beyond seem more relevant than ever.

Cite this article as: Wilson, A. (2024, March 5). ‘Lasting Legacies of Oman’s Anticolonial Revolution.’ Institute of Middle East, Caucasus and Central Asian Studies. https://mecacs.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/2024/lasting-legacies-of-omans-anticolonial-revolution-a-seminar-with-alice-wilson/.