MECACS Student Essay Prize – Honourable Mention (Honours)

Joseph Cryan is a fourth year student in the School of History. This essay received an Honourable Mention in the Honours section of the 2023 MECACS Student Essay competition.

To what extent did the Achaemenid empire enjoy the Rule of Law?

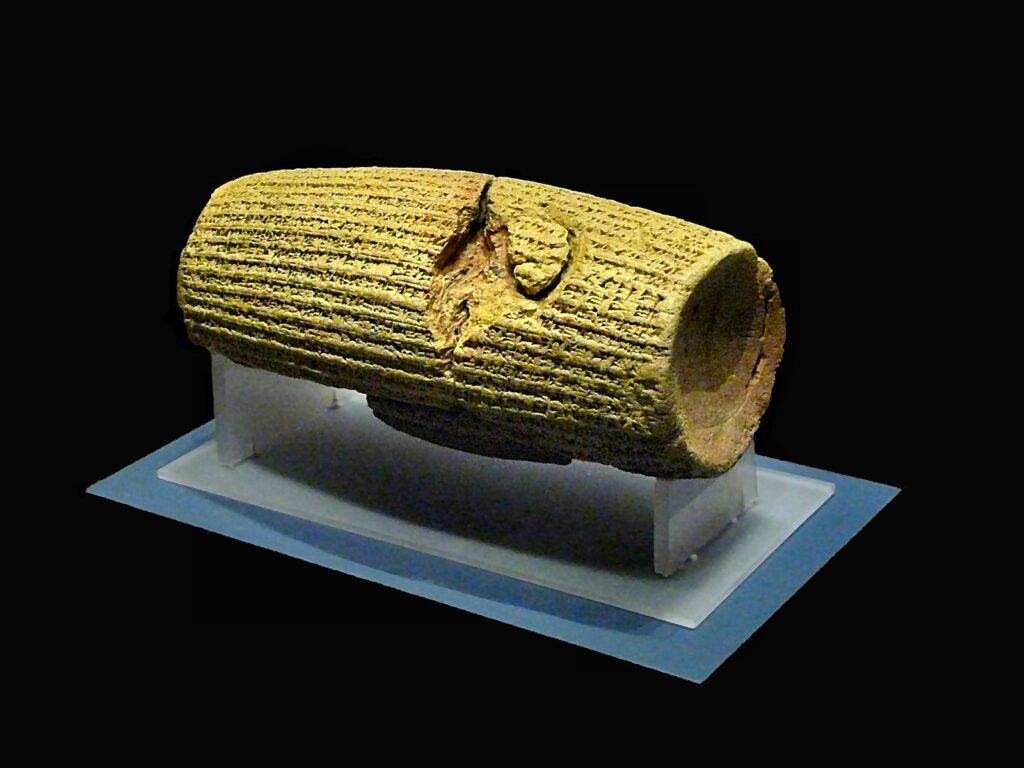

Much hay has been made out of the claim that the Cyrus Cylinder from Babylon was the world’s first “declaration of human rights”. The last Pahlavis presented a copy to the United Nation in order to promulgate the interpretation of the cylinder as evidence that Cyrus the Great was an enlightened ruler who governed his empire through consent and tolerance rather than fear and force.[1] Nonetheless, this argument has also been contested as oversimplifying the situation and placing too much emphasis on what was merely a statement setting out Cyrus’ legitimacy as king of Babylon, showing his devotion to the great god Marduk and his commission to restore peace and prosperity.[2]

This dichotomy of intent shows the difficulty with asking the question to what extent the Achaemenid Empire enjoyed the rule of law, restricted by the source material as we are. Nonetheless, this essay will argue that while the Achaemenid Empire was one of the most sophisticated societies of the Middle Eastern ancient world, and one that is sadly overlooked in the modern western zeitgeist, it would be inaccurate to describe the legal and judicial state of the empire as “the rule of law”. The rule of law can be briefly summarised in three broad elements. Firstly, legality and legal certainty, secondly, legal equality and fundamental rights and finally, judicial independence and access to justice.[3] This essay will analyse each of these three criteria and argue that although there may be elements of each present within Achaemenid government, none of the three were sufficiently established to classify the Achaemenids as a polity that enjoyed the rule of law.

Beginning with the first category – for the rule of law to exist in a state, that state has to abide by legality and legal certainty. Legality is simply the concept that the state can and should only act within its powers. Legal certainty is the principle that the law must be clear and must be publicly accessible.[4] Achaemenid ideology contradicted these principles in a number of ways. For example, as the Great King was the fount of authority and righteousness (rāsta) in the empire, the dāta (code or king’s authority that governed social relations between the classes and ethnic groups of the empire) was viewed as belonging to the Great King personally due to his commission from Ahuramazda.[5] Therefore, any actions against the wishes and policies of the Great King were inherently the actions of an agent of drauga (falseness or rebellion). In this way the Persian royal state that was overlaid on top of local institutions cannot be said to enjoy strict legality because there was no legal restriction on the powers of the Great King.

Furthermore, this connects with the problem of legal certainty. The Achaemenid state was a highly bureaucratised polity that very effectively created and stored records of transactions such as reimbursement for messengers on the transport system and receipts for debts owed to various merchants (especially to the famous Murushu banking family).[6]Nonetheless, the state did not have a centralised codified system of laws that could be accessed by anyone, let alone the average inhabitant of the empire. Instead, as previously mentioned, the laws of the kingdom operated on two levels, the “Persian laws” for the whole empire and the local laws. The city of Persepolis played a role as an administrative centre where Darius I most probably set out his reformation of the Persian laws which were then copied and distributed to the satrapal centres. [7] While this is certainly more sophisticated than most ancient polities in terms of legal development, it is far from meeting the criteria of a state run according to the rule of law. The possibility of an inhabitant of the empire having access to and knowledge of the laws that governed the kingdom would rely on them being close to the centre of imperial power at Persepolis or the peripatetic court or being literate in Aramaic and involved with local government. The first of these possibilities would almost certainly exclude all non-Persian inhabitants of the empire as the highest levels of imperial governance were restricted to Persians of noble birth. The second possibility would be limited to the local elites and their staff, far from the breadth required for the true rule of law.

This neatly bridges to the second category of definition for the rule of law. Indeed, the Achaemenid Empire was perhaps weakest in conforming to our modern standards of the rule of law when it comes to the criteria of legal equality and fundamental rights. This is because the unlike the Romans or Seleucids who succeeded them, the Achaemenid empire was almost exclusively controlled by a dominant socio-ethnic class of noble Persians who monopolised imperial power and office.[8] This class was made up of the royal family itself alongside the satraps and the Persian landowning elite across the breadth of the empire. Indeed, the Achaemenids are not alone in this, many states throughout history have restricted access to justice based on ethnic criteria, be they explicit or implicit. For example, the Democratic party in post-Reconstruction United States of America ensured their control over the Southern states through complex patronage networks and restricted franchises which denied black people their vote according to the fourteenth amendment.[9] While the Achaemenids had no such clear and legislated disenfranchisement of the non-Persian inhabitants of the empire, it is nonetheless clear that not all inhabitants held the same rights in the eyes of the law because of the stratified social and ethnic relations of the time. However, it must be said that the Achaemenid system inherited and continued many of the traditions of the near-eastern legal tradition such as property rights and the rather wide franchise of people with the ability to sue.[10] All this notwithstanding, the inhabitants of the empire clearly did not hold the same legal status. For example, women were allowed to bring suits to the inquisitorial courts but only when it pertained to women’s issues e.g., their dowries. Slaves and freedmen were allowed to bring suit when it pertained to their status as slave or freedman. This is in contrast to free men who could bring suits at any time. Furthermore, the individual components of a family unit would often be subordinated to the paterfamilias similar to the Roman concept of familial representation rather than individual legal equality. Further supporting this understanding of the inherent inequality of citizens, is the presence of records delineating inhabitants into categories of “weak” versus “mighty”.[11]

This shows that although once again the Achaemenids were somewhat ahead of the game in the sophistication of their legal system and continued to develop and build on previous traditions, their system cannot be fairly described as the rule of law because all inhabitants did not share legal equality. This is also connected to the integral issue of fundamental rights. In Britain, (the common poster child for a society predicated on the rule of law), the fundamental rights of citizens to trial by a jury of their peers, the right to habeas corpus and many other rights and protections have long and repeatedly asserted by the courts and successive governments for almost a millennium.[12] In the context of the modern German Rechtsstaat, many of the German citizen’s rights are established in the Grundgesetz and cannot be removed by legislative force.[13] In contrast, the Achaemenid empire continued the traditions of the near east by maintaining the practice of private law as it took form under the various subjugated peoples, (of which the Babylonians are the best attested). This meant that the citizens themselves did not have fundamental rights established by the law, indeed what we see from the remarkable unity of ancient near eastern legal culture is that these were instead societies mainly focussed upon the fundamental obligation of the citizens rather than their fundamental rights and protections. For example, one of the most important elements of near eastern adoption law was that it created a fundamental obligation on the adopted (and therefore legitimate) offspring to care for the parent in their dotage.[14]

Finally, coming to the third category of the rule of law, the importance of judicial independence and access to justice. The most contested of the three categories in modern societies that proclaim to be governed by the rule of law, judicial independence is difficult to quantify. States that are usually recognised as enjoying the rule of law can and do disagree on the definition and extent to which they themselves and others maintain judicial independence. For example, Hungary and Poland in the twenty-first century are both established democracies and member states of the European Union. Nonetheless, both states have taken actions that are viewed by themselves as increasing the democratic strength of the people but are viewed from outside as eroding the independence of the judiciary.[15] In addition there is the infamous British example from November 2016 when the Lord Chancellor Liz Truss failed to defend the three judges of the High Court of England and Wales against the epithet of “enemies of the people” by the right-wing tabloid The Daily Mail.[16]

With such discord in the modern era among countries that are quite uncontroversially said to enjoy the rule of law over judicial independence, it might be said that it is too much to expect the Achaemenid state to engage with this difficult criterion. Nonetheless, the Achaemenid system falls short of this element in a number of ways. Firstly, the judges of a court were made up of a variety of officials such as priests and local administrators, not professional men of the law and therefore were firmly integrated into the governmental structures. Secondly, the system was inquisitorial rather than adversarial so the judges would often be involved with gathering evidence and eliciting testimony. Finally, the division between secular and temple courts inevitably meant that judges were responsible to authorities above them outside the bounds of the legal profession (be that higher priests or royal officials), meaning that their judgements could be quite easily influenced and pressured.[17]

In conclusion, the Achaemenid empire was a highly advanced civilisation that helped build on pre-existing near-eastern legal traditions and certainly continued the development of what we now call the rule of law by defending property rights and establishing clear procedures for trials over a vast geographic area. Nevertheless, the desire to cast the Achaemenids as the progenitors of human rights who ruled over a stable and tolerant multi-ethnic empire with liberty and justice for all is an anachronistic and idealistic interpretation. Although the rule of law is a fluid and unclear concept even today, the lack of strict legality in the formulation of new law, the lack of legal certainty, the codified legal inequality of citizens and a lack of judicial independence means that despite their obvious sophistication the Achaemenids cannot be said to have created a polity that enjoyed the rule of law.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland.

Kuhrt, Amélie, The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period, (London, 2010).

– Kuhrt 14 B 31 ii

United Nations Gift Collection, ‘Replica of “Edict of Cyrus”’, United Nations Gift Collection, United Nations, <https://www.un.org/ungifts/replica-edict-cyrus> [accessed 28th June 2023].

Secondary Sources

Beckman, Daniel ‘Law, Mercy, and Reconciliation in the Achaemenid Empire’, Journal of Ancient History, Vol 8, Issue 2, (2020), pp. 127-151.

Briant, Pierre, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, (Winona Lake, 2002).

Daniel, Elton L., The History of Iran, (Westport, 2001).

Farbey, Judith, Sharpe, R. J., and Atrill, Simon ‘Historical Aspects of Habeas Corpus’, in Judith Farbey et al. (eds), The Law of Habeas Corpus, (Oxford, 2011), pp.1–17.

Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth, ‘False Friends and Avowed Enemies: Southern African Americans and Party Allegiances in the 1920s’, in Jane Dailey, Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore and Bryant Simon (eds), Jumpin’ Jim Crow: Southern Politics from Civil War to Civil Rights, (Princeton, 2001), pp.219-238.

James, Lisa and van Zyl Smit, Jan, ‘The Rule of Law: What is it and Why Does it Matter?’, Constitutional Principles and the Health of Democracy, Briefing 5, (December 2022).

Kuhrt, Amélie, The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period, (London, 2010).

Magdalene, F. R., On the Scales of Righteousness: Neo-Babylonian Trial Law and the Book of Job, (Providence, 2007).

Magdalene, F. R., “Achaemenid Judicial and Legal Systems,” Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. XV, Fasc. 2, p.173, an updated version is available at <https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/judicial-and-legal-systems-i-achaemenid-judicial-and-legal-systems> (accessed 29th June 2023).

Oelsner, Joachim, Wells, Bruce, and Wunsch, Cornelia, ‘Neo-Babylonian Period’, in Raymond Westbrook (ed.), A History of Ancient Near Eastern Law, Vol 2, pp.911-974

Slack, James, ‘Enemies of the People’, The Daily Mail, London, 4th November 2016.

Westbrook, Raymond, ‘The Character of Ancient Near Eastern Law’, in Raymond Westbrook (ed.), A History of Ancient Near Eastern Law, Vol 1, pp.1-90.

Wiesenhöfer, Josef, trans. Azizeh Azodi, Ancient Persia: from 550 BC to 650 AD, (London, 2001).

[1] United Nations Gift Collection, ‘Replica of “Edict of Cyrus”’, United Nations Gift Collection, United Nations, <https://www.un.org/ungifts/replica-edict-cyrus> [accessed 28th June 2023].

[2] Elton L. Daniel, The History of Iran, (Westport, 2001), p.38

[3] Lisa James and Jan van Zyl Smit, ‘The Rule of Law: What is it and Why Does it Matter?’, Constitutional Principles and the Health of Democracy, Briefing 5, (December 2022), p.1

[4] Ibid, p.2

[5] Daniel Beckman, ‘Law, Mercy, and Reconciliation in the Achaemenid Empire’, Journal of Ancient History, Vol 8, Issue 2, (2020), p.129

[6] Amélie Kuhrt, The Persian Empire: A Corpus of Sources from the Achaemenid Period, (London, 2010), p.717

[7] Josef Wiesenhöfer, trans. Azizeh Azodi, Ancient Persia: from 550 BC to 650 AD, (London, 2001), p.21

[8] Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, (Winona Lake, 2002), p.334

[9] Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, ‘False Friends and Avowed Enemies: Southern African Americans and Party Allegiances in the 1920s’, in Jane Dailey, Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore and Bryant Simon (eds), Jumpin’ Jim Crow: Southern Politics from Civil War to Civil Rights, (Princeton, 2001), p. 224

[10] F. R. Magdalene, “Achaemenid Judicial and Legal Systems,” Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. XV, Fasc. 2, p.173, an updated version is available at <https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/judicial-and-legal-systems-i-achaemenid-judicial-and-legal-systems> (accessed 29th June 2023).

[11] Joachim Oelsner, Bruce Wells and Cornelia Wunsch, ‘Neo-Babylonian Period’, in Raymond Westbrook (ed.), A History of Ancient Near Eastern Law, Vol 2, p.927

[12] Judith Farbey, R. J. Sharpe, and Simon Atrill, ‘Historical Aspects of Habeas Corpus’, in Judith Farbey et al. (eds), The Law of Habeas Corpus, (Oxford, 2011), p. 12

[13] Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Article 19

[14] Raymond Westbrook, ‘The Character of Ancient Near Eastern Law’, in Raymond Westbrook (ed.), A History of Ancient Near Eastern Law, Vol 1, p.51

[15] James and van Zyl Smit, ‘The Rule of Law’, p.3

[16] James Slack, ‘Enemies of the People’, The Daily Mail, London, 4th November 2016, p.1

[17] F. R. Magdalene, On the Scales of Righteousness: Neo-Babylonian Trial Law and the Book of Job, (Providence, 2007), p.65